Biala and de Kooning

Biala, “Le Duo,” 1945, oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 25 5/8 in (91.8 x 65.1 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala

This fall, Christie’s New York will offer works by Willem de Kooning formerly from the collection of Janice Biala and Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein. Biala and Alain were among Willem de Kooning’s earliest patrons.

Visit Christie’s to learn more about these works.

Janice Biala emigrated to the United States from Russian-occupied Poland in 1913 with her older brother, Jack Tworkov. As adolescents, the siblings decamped to Greenwich Village and became immersed in the bohemian life. Like her brother, Janice is an avid reader, with The Three Musketeers being her favorite book. She would later tell French novelist and art theorist André Malraux that it was because of Porthos that she became an artist. During a fateful trip from New York to Paris in 1930, Biala met and fell in love with the English novelist Ford Madox Ford. A formidable figure among writers, artists and the transatlantic intelligentsia, Ford introduced Biala to the many artists within his circle forging a new Modernism in France including Constantin Brancusi, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein. Upon Ford’s death in 1939, Biala fled Europe under the growing Nazi threat, rescuing Ford’s personal library and manuscripts while carrying as much of her own work as she could.

Re-establishing herself in New York City, Biala met and married the Alsace-born Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein. The couple became a fixture among the rising avant-garde artists living and working around Washington Square. Through her brother, Jack Tworkov, Biala met Willem de Kooning who had built out studio space in a second-floor walkup at a storefront at 85 Fourth Avenue and was renting half to Tworkov. Tworkov and de Kooning had met originally while working for the WPA during the 1930s.

“De Kooning didn’t seem to be painting much then,” Tworkov told de Kooning biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, “but toward the end of the thirties, [he] began to work a great deal and I began noticing it. At that time some of us began to think that he was a great artist, and we became friendly.”

Biala and Alain in a public square in Paris, c. 1948. Courtesy Tworkov Family Archives, New York

As offered by Stevens and Swan:

So glowing was the description of de Kooning that Biala immediately took an interest in the Dutchman’s art. Soon, she met and married an artist named Alain (Daniel) Brustlein, whose cartoons regularly appeared in The New Yorker. ‘So when Alain and I were married, Alain said, “Well, if (de Kooning’s) as good as you say he is, and if I like his work, I’ll buy one of his pictures,’” said Biala […] “So sure enough we went over there to de Kooning’s loft and he saw a picture [an abstract painting of 1938] that he liked and he bought it. This was probably in 1942.” – de Kooning: An American Master (New York: Alfred A. Knopf) p.177

Abstract Still Life (c.1938) is considered among the most rare and informative early paintings still in private hands. The work was included in a historic survey of de Kooning work at the Museum of Modern Art, organized by Thomas Hess in 1968. The painting is featured in the publication accompanying the exhibition as Hess describes:

“In his abstractions the space is a flat, slippery, metaphysical surface, related to that of some Mirós of the middle thirties; there are also recollections of Arp. The forms are based on the strip (usually vertical, related to Mondrian) and circles that have been forced into pointed or bulging ovals by the irregular pressures between shapes. This lateral pushing and pulling is held flat to the surface by bright colors (often keyed to blue and pink with parallel grays and ochers); their values are so close that, in Fairfield Porter’s phrase, they make 'your eyes rock.’” (p.25)

Abstract Still Life (c.1938) was not the only work by de Kooning that Alain and Biala would acquire. Because of Alain’s notoriety as an illustrator for The New Yorker, the couple had the means and would become important early patrons of de Kooning's work. “We bought a number of pictures from de Kooning because he needed the money.” Biala told Stevens and Swan. (p.177) And according to Stevens and Swan, Biala and Alain didn’t behave as most collectors did, trying to get the best possible price. “We’re not collectors,” Biala said, “We paid him the regular price. We were the only people who did that, Bill told Alain. We bought Woman [a turquoise and pink painting of 1944] and paid $700 for it, which at the time was a pretty good price.” (p.177)

de Koonings painting “Abstract Still Life” can be seen here, upper left in her own painting which features Alain playing the cello and Eliane de Kooning playing the piano.

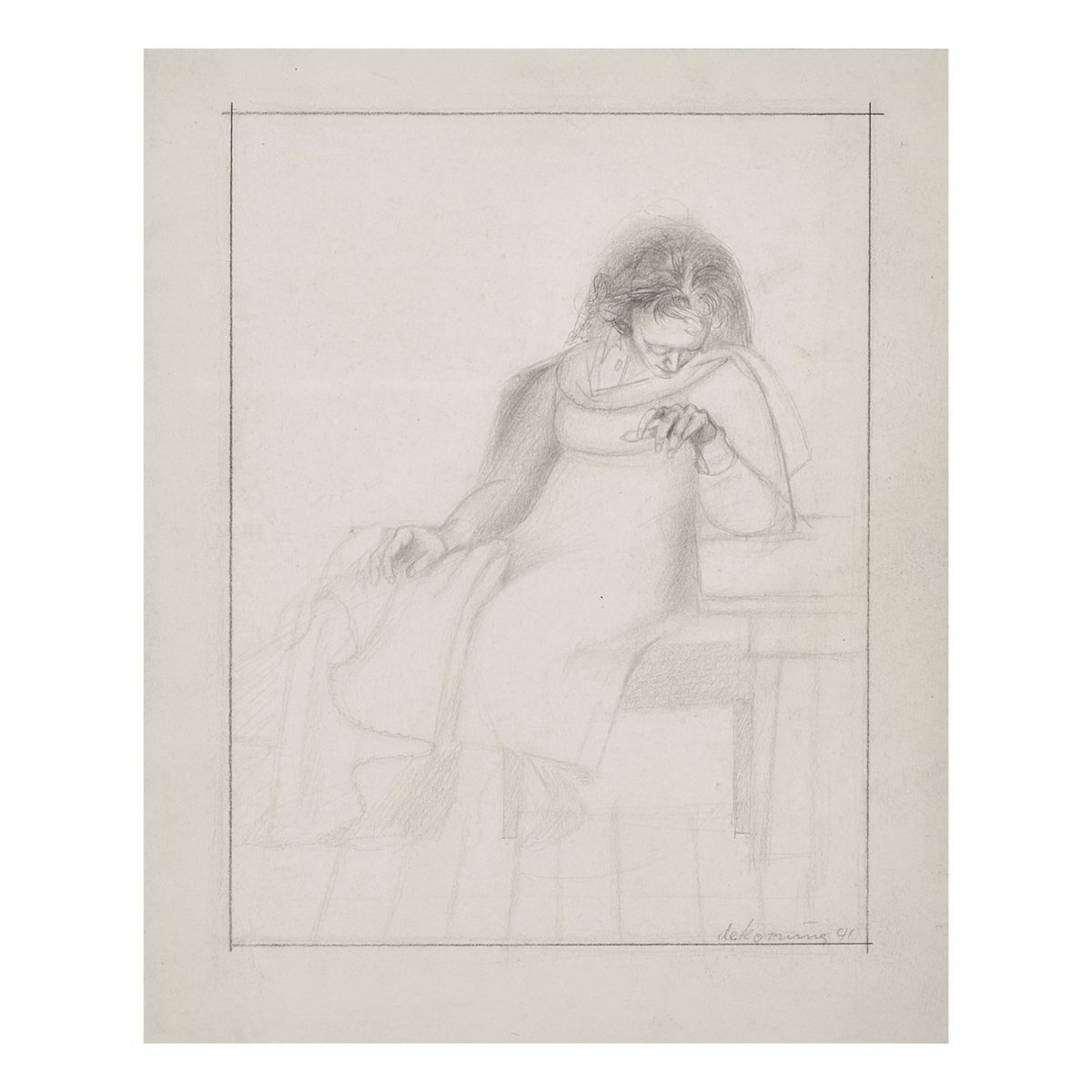

Beyond supporting de Kooning through the purchasing of work directly from the studio, Biala worked tirelessly to find him a gallery. She would introduce him to her own dealer, Georges Keller, who was the director of the Bignou Gallery credited for introducing modern French painting like Bonnard, Cézanne, Corot, Dufy, Matisse, Picasso, and Renoir to New York collectors. “It took me years to get Keller to come down to see his paintings,” said Biala. “Then he did, and he was very impressed. He took two paintings and three drawings.” (p.179) And yet, the best Keller would do was include de Kooning in a “quiet group exhibition of 1943,” which paled in comparison to the riotous rage made by the rise of Surrealism. When Bignou closed in 1949, he gave Biala, with de Kooning’s permission, the three drawings. It is believed that these drawings are Study for ‘Glazier’ (c.1938-39), Untitled (Massacre Scene) (1941), and Seated Woman (1941).

When de Kooning married Elaine Fried on December 8, 1943, it was Biala and Alain who hosted a “spontaneous, informal and extremely simple wedding lunch at a cafeteria.” Making the otherwise “bleak” event more celebratory. (Stevens and Swan, p. 197)

The many paintings and drawings by de Kooning that were acquired by Biala and Alain, hold historic significance; reflecting not only a sharp scene of connoisseurship, but the impeccable provenance of an intimate friendship.

Willem de Kooning, “Figure,” 1944, oil on Masonite, 19 1/2 x 16 1/8 in. Formerly from the Collection of Janice Biala and Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein

Essay: Hurly-burly Intimism: The Art of Janice Biala

Biala, Table Chargee, 1963, Torn paper collage with paint on canvas, 25 x 51 in. (63.5 x 129.5 cm)

The painter Janice Biala (1903-2000), known to history primarily by her surname, was an integral figure in the art scene of mid-twentieth century Manhattan. Sister of painter Jack Tworkov, friend of Willem de Kooning and critic Harold Rosenberg, Biala was in the thick of a milieu that gave rise to the New York School. While not an Abstract Expressionist per se, she was shaped by its hardscrabble verities. Biala’s artistic process, whether embodied in zooming brushstrokes or an agitated flurry of ripped paper, is unimaginable without them.

Biala didn’t yield to abstraction. Things in the world–concrete objects we hold, traverse or trip over–were her art’s impetus and end-point. The ages old endeavor of working from life puts Biala’s achievement at odds with prevailing notions of avant-gardism, of forward momentum and innovation. But looking at her pictures of unapologetic domesticity—Biala’s immediate surroundings served as inspiration–you wonder why the improbable marriage of de Kooning’s hurly-burly and Edouard Vuillard’s intimisme shouldn’t, in and of itself, be considered radical. At the very least, it’s a tough row to hoe.

The tension between pure abstraction and the everyday accrues most bluntly in Biala’s collages. Forget Kurt Schwitter’s loving accumulations of detritus or Max Ernst’s adroitly choreographed absurdities–a Biala collage like Vitrine (c. 1961) storms with impatience; scraps of paper, roughly geometric in form, align along a barely discernible grid. Elsewhere, an arcing tumble of tawny swatches coalesce into a tangible shape–a seated figure. An abrupt swipe of rust-red oil paint coupled with rambunctious shards of tan paper ultimately reveals a parent and child. The collages aren’t strictly representational, but the specificity of motif is felt as underlying structure–Biala captures its heft and integrity, albeit in abbreviated or obscured manner.

At other moments, Biala was considerably more deliberate and the resulting images are readily apparent–a stately clatter of houses in Provincetown, say, or the blocky effigies of a pianist and a cellist in the whimsical Untitled (The Concert) (c. 1957). Whatever speed she was traveling or however brusque the composition, Biala remained true to the world out there.

Biala’s investigations into collage would never reach the same level of intensity as they did during the years 1955-1960. In this tight knit group of works, we see her channeling Matisse’s élan, Braque’s unassuming virtuosity and we feel her debt, grateful and profound, to Velazquez. In each of the collages, you experience the heady excitement of an artist tussling with process, precedent and the unexpected poetry of the everyday.

This essay was originally published in the catalogue accompanying Biala: Collages 1957-1963, a 2009 exhibition at Tibor De Nagy Gallery.