Biala in Paris: Galerie Pavec (Oct 21-Dec 20)

JANICE BIALA, Vue de l'exposition L'esprit français, 2025. © Aurélien Mole

“I’d have no use for Paradise if it wasn’t like France.” — Biala, Letter to Jack Tworkov, December 3, 1947

Galerie Pavec is pleased to announce the first solo exhibition in Paris in thirty-eight years of the celebrated ex-pat painter Janice Biala. The exhibition “Biala: l’espirt Français” spans four decades and focuses on several of the artist’s most revered themes—still life, interiors, and street views. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue featuring a foreword by Pauline Pavec, an introduction by Biala scholar Jason Andrew, and a reprint of a rare 1952 essay by the noted French art critic Guy Weelen.

Biala (b. 1903, Biala, Poland; d. September 24, 2000, Paris, France) was a Polish-born American painter known in Paris and New York for her sublime assimilation of the School of Paris and the New York School of Abstract Expressionism. During her eight-decade career, her work was characterized by a modernist reinterpretation of classical themes of landscapes, still-life, and portraiture, animated gesturally with punctuated brush work held fast by her keen eye for observation.

At Galerie Pavec, we are committed to bringing back into the light singular artists, often women, whose importance has not been fully recognized by history. It is in this spirit that Biala’s work immediately found a resonance in me. Her work immediately struck me with its strength, its independence, and the way it bridges two artistic worlds: Paris and New York. Biala embodies this transatlantic dialogue that shaped the entire twentieth century and it’s thrilling to bring this work back to Paris.

– Pauline Pavec, Galerie Pavec

Paris played a vital role in shaping her life and art, serving as both a creative haven and a lifelong muse. She told the French novelist and art theorist André Malraux it was because of Porthos, the protagonist of The Three Musketeers, that she became an artist. She first arrived in Paris in April 1930, and through a fateful encounter met the English novelist Ford Madox Ford with whom she lived and collaborated. Seizing the time and the opportunity, Biala immersed herself in the thriving artistic and intellectual community in Paris and identified herself more broadly with European culture. She forged life-long relationships with modernist giants like Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, George Antheil, Constanti Brancusi, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso.

Biala was fierce, bold, and self-determined, and Paris offered her freedom and inspiration—a stark contrast to the constraints she experienced as a woman in America. The streets, the cafés, and the light of Paris infused her work with a unique lyrical clarity. Even after the death of Ford and her heroic escape from the Nazi regime at the onset of World War II, Biala longed for Paris, eventually booking passage on one of the first passenger vessels allowed to return after the war.

Janice Biala, “Intérieur (roses et fleurs),” 1966, oil on paper laid down on canvas, 16 ½ x 22 in (43.2 × 55.9 cm)

She eventually settled permanently in Paris as a legendary American expat. In the studio, Biala found herself at the intersection of the School of Paris and the New York School of Abstract Expressionism—aesthetic approaches she knew firsthand. In 1949, Biala received a special honorable mention in the Prix de la Critique—the first time a foreigner earned the award. The distinctiveness of the work aligned her with major galleries and gallerists like Jeanne Bucher (Galerie Jeanne Bucher), Jean-Robert Arnaud (Galerie du Point Cardinal), and Galerie Jacob to name a few. Biala’s work can be found in the collections of the Centre National des Arts Plastiques (CNAP), the Centre Pompidou (MNAM-CCI), the Fonds Régionaux d’Art Contemporain (FRAC), Musée de Grenoble, the Musée Ingres Bourdelle, and more recently the collection of Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins among others.

For Biala, Paris wasn’t just a backdrop; it was central to her identity as an artist and intellect. The city’s architecture and rhythm appear throughout her work, often not in literal depictions, but through a distinctly personalized sense of balance, clarity, and lyricism. Until her death in 2000, Paris remained Biala’s spiritual and creative home—a city where her artistic vision matured, flourished, and ultimately found its most resonant expression.

It has been thirty-eight years since the last solo exhibition of Biala’s work was organized by a gallery in Paris. This exhibition celebrates the artist that near left.

— Jason Andrew, 2025

Jason Andrew in conversation with Galerie Pavec.

BIALA: l’esprit Français

October 21-December 20, 2025

Opening receiption: Tuesday, October 21, 6:30-8:30pm

Galerie Pavec

4 rue de Jarente

75004, Paris

Exhibition News: Biala at Frieze Masters (Oct 15-19)

Berry Campbell is pleased to present Janice Biala: An American in Paris, a solo exhibition of paintings by Janice Biala (1903-2000) for the Spotlight section of Frieze Masters 2025. This presentation marks the first solo survey of Biala in London, a city she first visited in the early 1930s with her companion the English novelist Ford Madox Ford. Many of the works are on view publicly for the first time. We will feature seven important paintings from the 1950s and 1960s that are exemplary of Biala’s signature melding of styles and cultures. An American expatriate living in Paris, Biala developed a distinctive artistic language that embraced the formal innovations of the School of Paris while responding to the gestural intensity of postwar American painting. Mary Gabriel, The Ninth Street Women author, aptly described: “She existed between cultures, enriched by and enriching them all.”

Likened by many critics to the work of Maurice Utrillo and Albert Marquet for her affinity for painting cityscapes and still lifes, Biala’s work is known for its quiet intimacy and structural harmony. In each work, there is an emphasis on mood, light, and atmosphere, capturing everyday scenes with lyrical simplicity.

Three Figures (Trois personnage), 1952-53, oil on canvas, 37 ¾ x 57 ¾ in (95.09 × 146.7 cm)

Among the presentation is Three Figures (Trois personnages) (1952-53), a large dynamic work that contemporizes the genre of history painting. In it, Biala depicts the ballet historian Parmenia Migel Ekstrom, her Paris art dealer Jean-François Jaeger, and his wife in a blend of cubist structure and organic gesture. Untitled (Poitiers) (c. 1957) subtly engages with Impressionism, capturing the charm of a favorite French village on the river Clain. Nature morte au cremier Louis XVI (1952) presents a refined still life featuring a porcelain creamer collected during Biala’s relationship with Ford Madox Ford.

Biala’s work has garnered renewed institutional interest. Her work was recently featured in Action, Gesture, Paint (2023) at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, and Americans in Paris at the Grey Art Museum, NYU (2024). These exhibitions have affirmed Biala’s place within the broader narrative of postwar American abstraction, particularly in relation to women artists who operated between geographic and aesthetic boundaries. Biala’s work can be found in the collections of the Musée National d’Arts Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, among others.

This special exhibition is an extension of Berry Campbell’s gallery program, dedicated to the continued advancement of significant women artists.

FAIR LOCATION

The Regent’s Park, London

NW1 4HA

FAIR DATES

VIP Preview (Invitation Only)

Wednesday, October 15, 2025 | 11am - 7pm

Thursday, October 16, 2025 | 11am – 1pm

General Admission

Thursday, October 16, 2025 | 1pm – 7pm

Friday, October 17, 2025 | 11am - 7pm

Saturday, October 18, 2025 | 11am - 7pm

Sunday, October 19, 2025 | 11am – 6pm

Janice Biala: An American in Paris

Berry Campbell Gallery at Frieze Masters

Stand S20

October 15 - 19, 2025

The Regent’s Park, London

Booth Tour with Jason Andrew, Director of the Estate of Janice Biala

Sat, Oct 18, 2025, 1pm

Biala, Marsden Hartley, Ossip Zadkine, Valentine Prax and the 1938 Guggenheim Fellowship

L to R: Janice Biala, Marsden Hartley, Ossip Zadkine, and Valentine Prax. Copyright remains with respected entities.

Biala, Marsden Hartley, Ossip Zadkine, Valentine Prax and the 1938 Guggenheim Fellowship.

By Jason Andrew

Introductory text: In an unlikely comradery, this essay brings together the American painter Marsden Hartley and French painter Valentine Prax, the American-Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine and Janice Biala in her application to the 1938 Guggenheim Fellowship.

Biala with Ford at Villa Paul, c. 1936. Courtesy Estate of Janice Biala, New York

In 1938, Biala applied for a prestigious fellowship offered by the Guggenheim Foundation.[1] Having mounted several solo exhibitions both in New York and Paris, Biala was feeling confident and sought to apply, with the potential financial support aimed to help her continue to live, work, and travel in Europe.

In addition to listing her accomplishments, the application required references—individuals that could speak to the merits of her work. From her tiny three roomed cottage near Olivet College, Michigan, where her companion Ford Madox Ford was teaching literature, Biala wrote to three individuals to act as references: the painter Marsden Hartley, the sculptor Ossip Zadkine, and the painter Valentine Prax.

Writing to her friends, Biala made clear that the intention of her application was to support her on going work and travel in Europe. She was also felt that if awarded, the fellowship could help her standing in the art world. “There is a foundation called the Guggenheim in N.Y., which gives traveling bonuses to painters and others who have made a little mark and yet need boosting,” she wrote to Zadkine.

“I have been recommended to apply for one of these, for whether I’ve made a mark or not, I feel [a] great need for boosting […] They ask the applicants to give the names of people of distinction […] May I give your name as one? And it would be the greatest possible honor and pleasure if I could add that of Valentine Prax who was kind enough to say some kind words about my pictures when she saw them.”[2]

“Like Oliver Twist here, I am asking for more,” Biala wrote.

Letter from Biala to Zadkine, c.1938. Janice Biala Papers, 1903-2000. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. Copy of which in Tworkov Family Archives, New York.

The prior year, Zadkine wrote an introductory note alongside a foreword by Theodore Dreiser and additional text by Reid Anderson for a small folded brochure that accompanied Biala’s 1937 exhibition at Georgette Passedoit Gallery:

“Painting is not a matter of exteriorizing oneself but one of a most subtle absorption of the surrounding world, with the view of recording it and not of rendering it, as one would think, better or more beautiful […] Biala’s painting is of such; and being enhanced by an enlightening, intuitive quality, it creates a still more remarkable event.”[3]

Valentine Prax was a French painter noted for her expressionist and cubist paintings. She grew up in French Algeria, North Africa, where she studied at the Ècole des Beaux-Arts in Algiers. In 1919, she moved to Paris and rented a studio in 35 rue Rousselet. She was alone, timid and poor, but she was in Paris. She soon met Ossip Zadkine and they married in the summer of 1920. Responding to Biala’s request Zadkine wrote, “I will answer in the best possible manner. The same I can tell you on behalf of Valentine.”[4]

The third person Biala asked to support her application was the painter Marsden Hartley. Biala likely became acquainted with Hartley through her relationship with Ford. Ford and Hartley can be connected as early as 1918 when The Little Review published Hartley’s essay “The Reader Critic: Divagations” along with essays by Ford, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and William Butler Yeats among others.[5]

Their acquaintance was likely enhanced in 1924 when Hartley arrived in Paris and Ford, a rising literary figure among the transatlantic intelligentsia, was hosting crowded salons in his Paris apartment and editing the influential monthly literary magazine The Transatlantic Review.

Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) “After the Storm, Vinalhaven,” 1938-1939, 22 x 28 in (55.88 x 71.12 cm) Collection Bowdin College Museum of Art. Gift of Mrs. Charles Phillip Kuntz (1950.8)

Letter from Marsden Hartley to Janice Biala, October 15, 1938. Janice Biala Papers, 1903-2000. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. Copy of which in Tworkov Family Archives, New York

By the Summer of 1938, Hartley had moved to Vinalhaven, Maine, the largest of the Fox Islands located fifteen miles off the coast and home to a tightknit fishing community. Hartley responded to Biala in a typed letter on October 15, 1938. It was written towards the end of a challenging time for him at Vinalhaven. Hartley, whose biography does not describe the life of a warm and gregarious man, found the Vinalhaven people “one-dimensional” and wrote that he had never suffered so miserably ‘in both the physical and spiritual sense.”[6]

As Barbara Haskell wrote in the 1980 publication accompanying Marden’s retrospective at The Whitney Museum of American Art:

“All his life, Hartley had been plagued by dichotomous needs: a longing for crowds and, when painting, a desire for solitude and stark stretches of landscape. When he was in cities, he yearned for seclusion, yet when he was removed from the urban pulse, he found the isolation dispiriting.”[7]

Hartley had received a Guggenheim Fellowship himself in 1931 to study in Mexico. In his response to Biala he offered more than just his support. He spelled out his opinion of the committee, which he thought “a most conservative one,” and also gave a critique of her painting. “I don’t know of course what your pictures are like now, but it is to be assumed that you have progressed,” he prodded.

“I must be fair to myself however when I say that it was [your] graphic drawings that gave me the most pleasure, as I felt it was the graphic interest in the paintings that carried them over, the colour seemed to me a little halting, that is the emotional aspect of the colour itself seemed a little withdrawn, as if you had not let yourself quite go in it, and that is for me the first and last consideration, for the sense of colour is like the voice, and the fuller and richer and warmer it is the better a painting will be.”[8]

“Great Trade Route: It was the last remains of the golden age,” c.1936

Ink on paper 8 x 10 1/2 in. (20.3 x 27.9 cm) Signed lower right: "Biala"; Inscribed in pencil verso upper left: "No. 8 / It was the last remains of the golden age / half page 125"; Stamped verso: 1381

Private collection

“Great Trade Route: Put ‘em up against a wall,” c.1936

Ink on paper 11 3/4 x 9 3/4 in. (30.5 x 24.8 cm) Inscribed in pencil verso upper left and lower right by Shelby Cox: "Janice Tworkov ‘Biala’"; Stamped verso: 1381

Private collection

The ‘graphic interest’ Hartley gravitated to was in direct reference to Biala’s Spring 1937 exhibition at Georgette Passedoit.[9] Among the eleven paintings on view where the twenty-four original drawings that illustrated Ford Madox Ford’s novel Great Trade Route. Marsden’s statement about color is especially revelatory.

Hartley elucidated his feelings:

“I do not know what it matters at all what I think about other people’s work, but I always respond when I can and in the degrees in which I can, and in your case, I wonder how much the Americans will care, as how much do they care about any of us, and if they really did care I wouldn’t be up against such problems as I am, an awful life, the life of the artist anyhow, and I am about fed up on the American idea of it. At least the French make a real issue of it, and the practice of painting is an honorable one, no matter how poor the painting is.”[10]

This closing passage from Hartley’s letter sheds light on his temperament and arguments as an artist. Biala likely drew some consolation from his words—facing battles she, no doubt, was already managing, and as a woman artist.

There is no evidence that Biala successfully submitted her application, and it is certain that she was not awarded a fellowship. Of the fifty-eight Guggenheim Fellows awarded in 1938, only six were women: Katherine Anne Porter (1890-1980) author; Janet de Coux (1904-1999) sculpture; Lu Duble (1896-1970) sculpture; Rosella Hartman (1895-1984) painting; Virginia Randolph Grace (1901-1994) archaeology; Mary Catherine Gunning Colum (1884-1957) literary critic and author.

[1] Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since 1925 by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Not unaware of this grant opportunity, her older brother, Jack Tworkov, had applied in 1934 but his application wasn’t received in time to be considered, this would be the first and only time Biala would apply.

[2] Janice Biala to Zadkine, c.1938. Janice Biala Papers, 1903-2000. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. Copy of which in Tworkov Family Archives, New York.

[3] Ossip Zadkine. Exhibition introductory note for Georgette Passedoit Gallery, New York, “Paintings and Drawings by Biala,” February 23–March 13, 1937. Original can be found in the Tworkov Family Archives, New York.

[4] Ossip Zadkine to Janice Biala, c.1938. Janice Biala Papers, 1903-2000. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. Copy of which in Tworkov Family Archives, New York.

[5] “The Little Review” was an American avant-garde literary magazine founded in Chicago in 1914 by Margaret Anderson. It was known for its publication of experimental writing and art by prominent modernist authors, most notably the serialization of James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” VIEW HARTLEY’S ESSAY

[6] Hartley to Hudson Walker, October 8, 1938. Hudson D. Walker papers, 1920-1982. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[7] Barbara Haskell. Essay in Marsden Hartley (New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art; New York University Press, 1980) pp 114-115.

[8] Hartley to Biala. October 15, 1938. Janice Biala Papers, 1903-2000. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. Copy of which in Tworkov Family Archives, New York.

[9] Incidentally, Hartley’s own exhibition at Stieglitz’s An American Place would open one month after Biala’s running April 20-May 17, 1937.

[10] Hartley to Biala, October 15, 1938. Janice Biala Papers, 1903-2000. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. Copy of which in Tworkov Family Archives, New York.

Announcing exclusive representative of the Estate of Janice Biala

Biala at Galerie Denise René, Paris 1967. Photo: Yoshi Takata. Courtesy Estate of Janice Biala

Berry Campbell is pleased to announce the exclusive representation of Janice Biala (1903-2000). In April of this year, in collaboration with the Estate of Janice Biala, Berry Campbell organized the critically acclaimed solo exhibition Biala: Paintings 1946-1986. This survey featured 30 paintings and works on paper from the Estate of Janice Biala, highlighting several works that have not been on view since they were created. This exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated, 100-page catalogue featuring an introduction by Mary Gabriel and an in-depth essay by Jason Andrew, Director of the Estate of Janice Biala. As part of this announcement, the Estate released this statement:

“This collaboration marks an exciting new chapter in honoring Biala’s unique talent and extraordinary legacy. Berry Campbell’s deep appreciation for artists of Biala’s generation and beyond makes them an ideal partner, and we trust their expertise will elevate her profile and connect her with new audiences. We look forward to seeing Biala’s legacy thrive under their care.”

Berry Campbell recently sold a Biala painting as part of their presentation at The Armory Show and will include a rare early painting at The Art Show (ADAA). Additionally, Biala’s La Seine: Paris la Nuit, 1954, is on view at the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, Massachusetts, as part of the Americans in Paris: Artists Working in Postwar France curated by Debra Balken and Lynn Gumpert, co-organized with NYU Grey Art Gallery, New York. Biala is also featured in Seeing Red: Renoir to Warhol at the Nassau County Museum of Art, Roslyn, New York. Berry Campbell looks forward to a long and fruitful partnership with the Estate of Janice Biala.

Installation view, Janice Biala: Paintings 1946-1986, Berry Campbell, New York, 2024.

Article: Janice Biala’s epochal studio via Two Coats of Paint

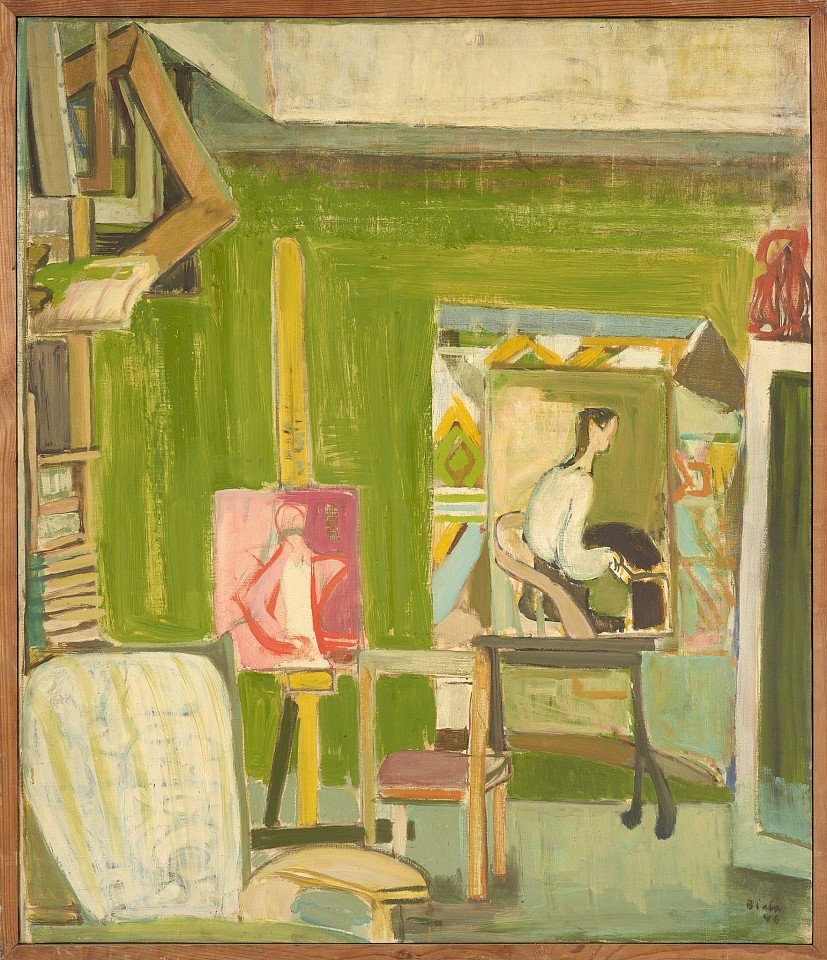

Janice Biala, The Studio, 1946, oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches

Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson

Published at Two Coats of Paint

April 6, 2024

A striking feature of the paintings and works on paper of Janice Biala (1903–2000), now on view at Berry Campbell in a show craftily curated by Jason Andrew, is their seamless reconciliation of civilizational clutter and spatial order. Fixing that notion is the earliest painting, The Studio (1946), arraying the artist’s active workspace and establishing her intent to embrace the world through it. (Coincidentally, Vera Iliatova’s “The Drawing Room” at Nathalie Karg gamely recaptures and updates kindred impulses.) Biala’s work here, spanning the immediate postwar period almost to the end of the Cold War and blending the New York School and the School of Paris – she lived in both cities – also bears the considerable weight of twentieth-century history, art and otherwise, with extraordinary grace and weightless cohesion, free of the strain of obvious contrivance.

Façade Blanche (White Facade), painted in 1948, depicts the physical strata of a Paris neighborhood with both due attention to detail and variegation and an implicit emphasis on the calmly agreeable organization of the visible environment, which is pointedly unoccupied. When Biala goes inside, as with Nature Morte à la Table (1948) and White Still Life (1951), she apprehends the material incidents of private life from a distinct remove, according them equal perspectival weight in cool tones that impart a sense of secure refuge within humanity’s sprawl and struggle. Even figures are absorbed into their inanimate surroundings. Jeune fille en rose, assise (Young girl in pink, sitting) is a moderate example, Two Young Girls (Hermine and Helen) a more extreme one verging on abstraction. The idea, it seems, is not the world’s erasure or engulfment but rather its harmonious accommodation of individuals, whatever their identities.

The trappings of Biala’s work are bohemian, not bourgeois, and it has a proletarian undercurrent. In Chevet de Notre Dame et l’ile St. Louis, 1949, the iconic church is iconoclastically painted from the rear, now a passive source of cultural comfort rather than an imposing summoning of faith or awe. Le Louvre (1948) is similarly down-to-earth, spied from the vantage of the Left Bank and settling humbly on the museum’s rooftop. Perhaps unsurprisingly, pieces from the mid to late 1950s, especially collages – see Violincelliste, Blue Parrot, and Untitled (Nature Morte) – are more abstract and suggestively gestural. Two drawings from the sixties – The Bather (Dana) and Study for “Blue Kitchen” – sunnily embrace the counterculture and 1960s modernism, respectively. Vaulting forward to the 1970s, the celebrated triptych Les Fleurs, isolating vases of flowers from separate perspectives, and Brown Interior with Rosine, presenting a woman sitting in drab comfort, assume a more austere, subdued, and regimented cast, perhaps a nod to the exigencies of age and the compulsion of preservation – or to fading glory.

It’s not too outlandish to say that Biala herself encapsulated the twentieth century, having lived 97 of its 100 years and tackled her vocation with versatility and virtuosity to match its historic eventfulness. She and her family – including her older brother, Abstract Expressionist painter Jack Tworkov – arrived in New York from Poland in 1913 and first lived in the tenements of the Lower East Side, which presumably attuned her early on to the tension between population and space. To distinguish herself from Jack, she took as her surname the name of the Polish town of her birth. She was the last romantic partner of the English novelist Ford Madox Ford, author of Parade’s End, a noted tetralogy on the First World War. After his death in 1939, Biala, at personal risk, extracted his manuscripts from Paris as the Nazis bore down. She experienced and absorbed the alternating currents of history, and on this score the two paintings on display from the 1980s seem telling in their divergence. Homage to Piero della Francesca is bright, busy, and elegiac – aptly enough, towards a Renaissance painter known for both his humanism and his geometric sense of order – while Black Still Life with Artichokes is contrapuntally dark, spare, and foreboding. From the studio, Biala perceived, as great artists often do, the promise and the peril of her time.

“Janice Biala: Paintings, 1946–1986,” Berry Campbell, 524 West 26th Street, New York, NY. Through April 13, 2024.

Exhibition News: Spotlight: Swiss Gallery Kutlesa’s New Show Is a Visual History of Abstraction

Installation view of "Exploring the Depths of Abstractionism" (2024). © The Artists/Estates. Photo: Annik Wetter. Courtesy of Kutlesa, Goldau, Switzerland.

Read on Artnet News.

What You Need to Know: On view through April 13, 2024, Kutlesa gallery in Goldau, Switzerland, is presenting the wide-ranging group exhibition “Exploring the Depths of Abstractionism.” Featuring the work of ten artists—Janice Biala, Lucy Bull, Michele Fletcher, Stefan Gierowski, Cyrielle Gulacsy, Zoe McGuire, George McNeil, Milton Resnick, Park Seo-Bo, and Jack Tworkov—the show brings together both historic 20th-century works and recent contemporary paintings. Using abstraction itself as a starting point, the exhibition traces the evolution of the technique and how artists use it to express ideas, emotions, and experiences outside the bounds of traditional modes of representation.

Why We Like It: On the whole, “Exploring the Depths of Abstractionism” at Kutlesa emphasizes the remarkable power that abstraction holds in its capacity to clearly convey—without figuration or representation—facets of everyday life and lived experience. The psychological and emotional elements are brought to the fore, providing a visual experience that transcends identifying symbols or illusory space. When looking closely at each work in the exhibition, however, abstraction as an invaluable and wholly unique approach for artists becomes apparent through juxtaposition. Abstraction become a personal language for the painter, which can offer insight into their own distinct practice as well as avenues of artistic exploration. While Zoe McGuire’s recent Crossing (2024) presents luminous, curving shapes of color that suggest a landscape just beyond the scope of recognizability, so too does Janice Biala’s midcentury masterwork Paris Night (1957), which offers an impression of a cityscape without concrete visual references. Similarly, Cyrielle Gulacsy’s CS021 (2024) uses a form of pointillism and total abstraction to convey impressions of light, which echoes the total abstraction of Hawkeye 12 (1972) by Milton Resnick, which blends flickers of color in overall black, letting the eye search for the muted presence of light and hue.

According to the Gallery: “Dansaekhwa luminary Park Seo-Bo’s meditative, process-driven work enters a meaningful dialogue with Gierowski’s harmonious fusion of precision and chromatic sensibilities. The dynamic range of Tworkov, McNeil and Resnick, all of the New York School, gains depth and resonance when paired with Janice Biala’s distinctive palette and tenor, rendered with the sweeping, gestural hallmarks of Abstract Expressionism. Interwoven with these seminal voices are the enigmatic and exploratory visions of Cyrielle Gulacsy and Lucy Bull; the poetic works of Michele Fletcher that oscillate between memory and landscape; and Zoe McGuire’s otherworldly universe, emerging from layers of color and light.

The virtues of these works, whether harmony, spirituality, pure gesture or simplicity, take on a collaborative, living form when presented alongside one another, finding renewed purpose and expansive potential within each viewer’s encounter and subjective perception.” –Sabrina Tamar

Article: How Artist Biala Left Her Mark on 20th-Century Modernism via Artnet

Janice Biala, Untitled (Orange Interior) (1967)

Published at Artnet

March 21, 2024

Every month, hundreds of galleries add newly available works by thousands of artists to the Artnet Gallery Network—and every week, we shine a spotlight on one artist or exhibition you should know. Check out what we have in store, and inquire for more with one simple click.

What You Need to Know: Presented by Berry Campbell, New York, in collaboration with the Estate of Janice Biala, “Biala: Paintings, 1946–1986” brings together more than 30 paintings—the largest showing of the late artist’s work in the city to date. The exhibition further marks the very first time many of the paintings are on view to the public. Accompanying the exhibition is a fully illustrated 100-page catalogue, featuring an essay by Manager and Curator of the Estate of Janice Biala, Jason Andrew, and an introduction by bestselling author Mary Gabriel, who also wrote Ninth Street Women (2018). “Biala: Paintings, 1946–1986” opens Thursday, March 21, and will be on view through April 13, 2024.

About the Artist: Janice Biala (1903–2000), born Schenehaia Tworkovska, maintained a unique practice that closely followed—and pioneered—the ideas and trends of 20th century transatlantic Modernism. Originally from the small city of Biała, Podlaska in the Russian occupied Kingdom of Poland, she immigrated to New York City in 1913. To assimilate, her parents changed her name to Janice; she later reclaimed the name of her birthplace, Biala, as her surname, and at the suggestion of artist William Zorach went by Biala as a mononym.

Developing a desire to become an artist at a young age, she went on to take courses at the National Academy of Design, the Art Student’s League, and trained under artists such as Charles Hawthorne and Edwin Dickinson. In 1930, she travelled to Paris, where she met and fell in love with English novelist Ford Madox Ford, who introduced her to many influential figures within the French art scene, including Gertrude Stein, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, to name a few. Following Ford’s death in 1939, and with the rising threat of Nazi invasion, she returned to New York.

Back in the city, she became a recognizable figure within the burgeoning avant-garde arts scene and one of the few women engaging with Abstract Expressionism. In 1955, the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired one of her works, the first institution to do so. Ultimately, her career spanned seven decades and two capitals of the art world, and is recognized as an imperative facet to the development of Modernism.

Why We Like It: Moving seemingly intuitively between abstraction and representation, the synthesis of elements from both the School of Paris and New York Abstract Expressionism is unmistakable. The exhibition of her work at Berry Campbell, which includes paintings dated from across a 40-year period, lets viewers visually accompany Biala through the trajectory of her artistic experiments and evolution. In early works like The Studio (1946), perspectival space is distorted but still very much discernable, offering a charming view into a green studio room. In works such as Red Interior with Child (1956) from a decade later, the depiction of space is largely relegated to the title of the painting, and the composition is overrun with swaths of vibrant pigment, with only the suggestion of a child on the right edge of the canvas. Her investigations into abstraction also didn’t stop with paint, as Casoar (The Cassowary) (1957) shows, made from collage comprised of torn paper with oil on canvas. The show is a testament to Biala being poised for not only reappraisal within the context of the art historical canon, but her singular contribution to the narrative and development of 20th-century Modernism.

Exhibition News: Americans in Paris at The Grey Art Museum (Mar 2-Jul 20)

Janice Biala (1903-2000) La Seine: Paris la Nuit, 1954, Oil on canvas, 18 x 36 3/8 in (48.3 x 92.4 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York

AMERICANS IN PARIS

Artist Working in Postwar France, 1946-1962

March 2-July 20, 2024

The Grey Art Museum

18 Cooper Square

NYC

Following World War II, hundreds of artists from the United States flocked to the City of Light, which for centuries had been heralded as an artistic mecca and international cultural capital. Americans in Paris explores a vibrant community of expatriates who lived in France for a year or more during the period from 1946 to 1962. Many were ex-soldiers who took advantage of a newly enacted GI Bill, which covered tuition and living expenses; others, including women, financed their own sojourns.

Showcased here are some 130 paintings, sculptures, photographs, films, textiles, and works on paper by nearly 70 artists, providing a fresh perspective on a creative ferment too often overshadowed by the contemporaneous ascendency of the New York art scene. The show focuses on a diverse core of twenty-five artists—some who are established, even canonical, figures, and others who have yet to receive the recognition their work deserves. A complementary section dubbed the “Salon” combines works by French and foreign artists that the Americans would have seen in Parisian galleries or annual salons, alongside examples by compatriots who likewise spent at least a year residing in France during this time.

While the U.S. art scene was dominated by the rise of Abstract Expressionism, Americans working in Paris experimented with a range of formal strategies and various approaches to both abstraction and figuration. And, as the esteemed writer James Baldwin—a longtime French resident—saliently observed, living in Paris afforded expats the opportunity to question what it meant to be an American artist at midcentury. For some, Paris promised a society less constrained by racism and the exclusionary power structures of the New York art world.

American artists also encountered undercurrents of nationalistic tension, as French critics sought to maintain Paris’s artistic preeminence. By 1962, the year that concludes the exhibition, many felt that the once-inspiring atmosphere had diminished. That same year, Algeria achieved independence from France after many years of demonstrations and riots, and, ultimately, war. Many Americans opted to return to the U.S., which was experiencing a burgeoning civil rights movement, and in particular to New York, where there were more opportunities to exhibit, due in part to the rise of artist-run galleries. Others chose to remain abroad. Whether they returned or remained in Paris, the Americans’ encounters with French collections, artists, critics, and gallerists significantly impacted the development of postwar American art.

Exhibition News: Biala / 40 yrs of painting at Berry Campbell (Mar 14-Apr 13)

Biala (1903-2000) "Le Louvre," 1948, oil on canvas, 36 x 28 1/4 in (91.4 x 71.8 cm) [CR753]

Biala: Paintings, 1946-1986

March 14 - April 13, 2024

Opening reception: Thursday, March 14, 6-8pm

Berry Campbell

524 West 26th Street

New York, NY 10001

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

_________

NEW YORK, NY – Berry Campbell and the Estate of Janice Biala are pleased to announce a major survey of paintings by Janice Biala (1903-2000). The survey featuring over 20 paintings dating from 1946 to 1986, marks the largest gallery exhibition of Biala's work mounted in New York City with many works on view for the first time. A fully illustrated 100-page catalogue accompanies the exhibition which includes introduction by Mary Gabriel, author of “The Ninth Street Women,” and essay by Jason Andrew, manager and curator of the Estate of Janice Biala. This historic presentation coincides with the Grey Art Museum’s seminal exhibition “Americans in Paris, 1946-1962: Artists Working in Postwar France, 1946-1962,” opening March 2 in which Biala will be featured.

"Portrait of Biala" photo by Henri Cartier-Bresson

© Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

One of the most inventive artists of the 20th Century, and the painter most closely aligned with the continuation of a transatlantic Modernist dialogue between Paris and New York, Janice Biala (1903-2000), led a legendary life: a painter recognized for her distinctive style that combined the sublime assimilation of the School of Paris and the gestural virtuosity of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism.

Biala rose from humble yet tumultuous beginnings as a Jewish immigrant from Russian occupied Poland arriving in New York in 1913 settling among the tenements of the Lower East Side. She claimed the name of her birthplace for her own, going on to make personal and unique contributions to the rise of Modernism both in Paris and New York.

Having spent the decade of the 1930s as the last companion to the English novelist, Ford Madox Ford, Biala was the perfect representative of American bohemia in 1930s France and her journey as an artist evolved in tandem with the historic events of the 20th century.

Highlighting this survey is a pivotal group of paintings dating from 1947 to1952. On view for the first time in New York, these works were painted by Biala upon her triumphant return to Paris in 1947 aboard the de Grasse, one of the first passenger transatlantic ships to sail from New York to Europe after World War II. Her return was also a joyous one, “I still find in France all the things I’d hoped for,” she wrote her brother Jack Tworkov, “I’d have no use for Paradise if it wasn’t like France.” These works offer an extraordinary opportunity to see Biala’s close connection to European Modernists like Picasso and Matisse, both of whom she had frequently met.

“Though her themes of still life and interiors, landscapes and portraiture remained constant, her approach to portraying them evolved,” writes Jason Andrew in essay for the catalogue accompanying the exhibition:

“Impressionism is a term rarely used in discussing Biala’s work, but it fits with her sensitivity and narrative. Never liberal with factual description in her paintings, Biala pulls us in through a balance of subtle truths—the hard edge of a table, the soft outline of a figure, the dark shadow of a building. It’s a tender abstraction that feels lived in, and one which she honed very early on from her mentor Edwin Dickinson and heightened by the vigilant study of the narratives crafted by Ford Madox Ford.”

Biala (1903-2000) "Nature Morte à la Table," 1948, Oil on canvas, 31 1/4 x 45 in (79.4 x 114.3 cm) [CR754]

“Le Louvre,” 1948, is among this group and one of the first paintings to fully capture the architecture of Biala's adopted city. A seminal work, the painting features a view of the city from the Left Bank looking North across the Seine with views of the Louvre and the Jardins des Champs-Élysées. More specifically, Pavillon de la Trémoille appears on the upper left and the various rooftops that make up the Louvre filling the horizon. Pont de Arts stretches horizontally through the painting’s center left. Framing the composition is an iron railing in the near foreground.

Alongside this historic group of paintings, Berry Campbell will present important large-scale works including multi-paneled paintings which bridge American and European traditions—portraying a synthesis of cultures and emotions. As an example, the two paneled work “Intérieur à grand plans noirs, blancs, rose,” 1972, on view for the first time, embraces Biala’s suggestive approach to space. “Here the continuity of reading the painting from left to right is deprioritized in order to offer multiple vignettes—evocative impressions and multiple views of an interior where angles are represented by juxtaposition of color,” writes Jason Andrew.

Biala (1903-2000) "Les Fleurs," 1973, acrylic on canvas (three parts), overall: 45 x 108 in (114.3 x 276.9 cm) [CR066]

In the epic three paneled painting “Les Fleurs,” 1973, three differing perspectives vie for sovereignty as each offers an individually composed interior with bold and blocked in color—bare of human presence. Here the flourishing potted flowers bring the personality.

The exhibition also features a gallery dedicated to Biala’s works on paper and in particular, her collage work. As the artist noted, towards the end of the 1950s, her transatlantic returns from Paris to New York took their toll on her paintings. So, she turned her attention to collage. Embracing the “immediate effects,” which “you can’t possibly get in painting,” Biala embarked on an intense exploration of the medium. The subjects in Biala’s collages range from intimate interiors to the wild and thrilling portrayal of a cassowary.

For checklist and press inquires: info@berrycampbell

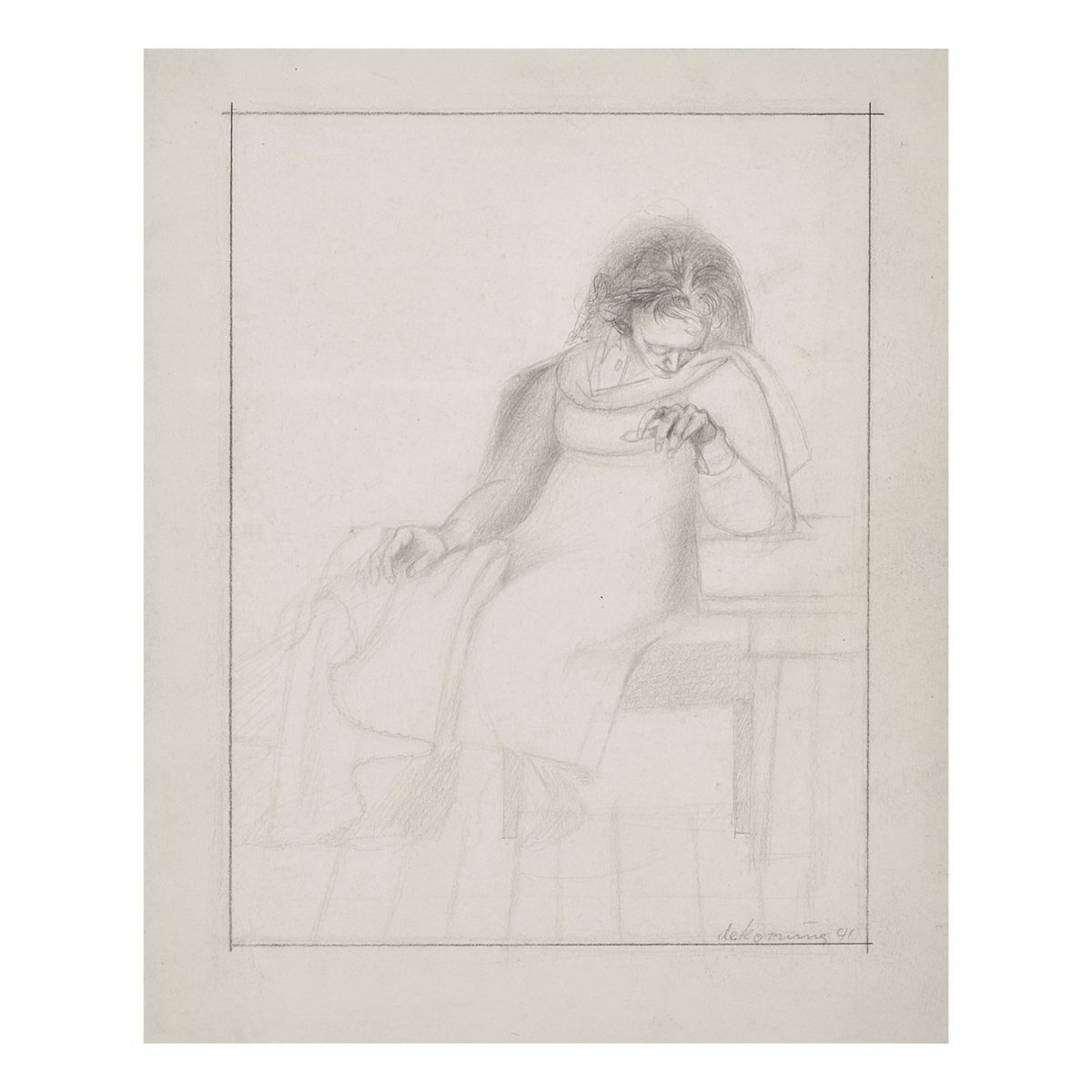

Biala and de Kooning

Biala, “Le Duo,” 1945, oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 25 5/8 in (91.8 x 65.1 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala

This fall, Christie’s New York will offer works by Willem de Kooning formerly from the collection of Janice Biala and Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein. Biala and Alain were among Willem de Kooning’s earliest patrons.

Visit Christie’s to learn more about these works.

Janice Biala emigrated to the United States from Russian-occupied Poland in 1913 with her older brother, Jack Tworkov. As adolescents, the siblings decamped to Greenwich Village and became immersed in the bohemian life. Like her brother, Janice is an avid reader, with The Three Musketeers being her favorite book. She would later tell French novelist and art theorist André Malraux that it was because of Porthos that she became an artist. During a fateful trip from New York to Paris in 1930, Biala met and fell in love with the English novelist Ford Madox Ford. A formidable figure among writers, artists and the transatlantic intelligentsia, Ford introduced Biala to the many artists within his circle forging a new Modernism in France including Constantin Brancusi, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein. Upon Ford’s death in 1939, Biala fled Europe under the growing Nazi threat, rescuing Ford’s personal library and manuscripts while carrying as much of her own work as she could.

Re-establishing herself in New York City, Biala met and married the Alsace-born Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein. The couple became a fixture among the rising avant-garde artists living and working around Washington Square. Through her brother, Jack Tworkov, Biala met Willem de Kooning who had built out studio space in a second-floor walkup at a storefront at 85 Fourth Avenue and was renting half to Tworkov. Tworkov and de Kooning had met originally while working for the WPA during the 1930s.

“De Kooning didn’t seem to be painting much then,” Tworkov told de Kooning biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, “but toward the end of the thirties, [he] began to work a great deal and I began noticing it. At that time some of us began to think that he was a great artist, and we became friendly.”

Biala and Alain in a public square in Paris, c. 1948. Courtesy Tworkov Family Archives, New York

As offered by Stevens and Swan:

So glowing was the description of de Kooning that Biala immediately took an interest in the Dutchman’s art. Soon, she met and married an artist named Alain (Daniel) Brustlein, whose cartoons regularly appeared in The New Yorker. ‘So when Alain and I were married, Alain said, “Well, if (de Kooning’s) as good as you say he is, and if I like his work, I’ll buy one of his pictures,’” said Biala […] “So sure enough we went over there to de Kooning’s loft and he saw a picture [an abstract painting of 1938] that he liked and he bought it. This was probably in 1942.” – de Kooning: An American Master (New York: Alfred A. Knopf) p.177

Abstract Still Life (c.1938) is considered among the most rare and informative early paintings still in private hands. The work was included in a historic survey of de Kooning work at the Museum of Modern Art, organized by Thomas Hess in 1968. The painting is featured in the publication accompanying the exhibition as Hess describes:

“In his abstractions the space is a flat, slippery, metaphysical surface, related to that of some Mirós of the middle thirties; there are also recollections of Arp. The forms are based on the strip (usually vertical, related to Mondrian) and circles that have been forced into pointed or bulging ovals by the irregular pressures between shapes. This lateral pushing and pulling is held flat to the surface by bright colors (often keyed to blue and pink with parallel grays and ochers); their values are so close that, in Fairfield Porter’s phrase, they make 'your eyes rock.’” (p.25)

Abstract Still Life (c.1938) was not the only work by de Kooning that Alain and Biala would acquire. Because of Alain’s notoriety as an illustrator for The New Yorker, the couple had the means and would become important early patrons of de Kooning's work. “We bought a number of pictures from de Kooning because he needed the money.” Biala told Stevens and Swan. (p.177) And according to Stevens and Swan, Biala and Alain didn’t behave as most collectors did, trying to get the best possible price. “We’re not collectors,” Biala said, “We paid him the regular price. We were the only people who did that, Bill told Alain. We bought Woman [a turquoise and pink painting of 1944] and paid $700 for it, which at the time was a pretty good price.” (p.177)

de Koonings painting “Abstract Still Life” can be seen here, upper left in her own painting which features Alain playing the cello and Eliane de Kooning playing the piano.

Beyond supporting de Kooning through the purchasing of work directly from the studio, Biala worked tirelessly to find him a gallery. She would introduce him to her own dealer, Georges Keller, who was the director of the Bignou Gallery credited for introducing modern French painting like Bonnard, Cézanne, Corot, Dufy, Matisse, Picasso, and Renoir to New York collectors. “It took me years to get Keller to come down to see his paintings,” said Biala. “Then he did, and he was very impressed. He took two paintings and three drawings.” (p.179) And yet, the best Keller would do was include de Kooning in a “quiet group exhibition of 1943,” which paled in comparison to the riotous rage made by the rise of Surrealism. When Bignou closed in 1949, he gave Biala, with de Kooning’s permission, the three drawings. It is believed that these drawings are Study for ‘Glazier’ (c.1938-39), Untitled (Massacre Scene) (1941), and Seated Woman (1941).

When de Kooning married Elaine Fried on December 8, 1943, it was Biala and Alain who hosted a “spontaneous, informal and extremely simple wedding lunch at a cafeteria.” Making the otherwise “bleak” event more celebratory. (Stevens and Swan, p. 197)

The many paintings and drawings by de Kooning that were acquired by Biala and Alain, hold historic significance; reflecting not only a sharp scene of connoisseurship, but the impeccable provenance of an intimate friendship.

Willem de Kooning, “Figure,” 1944, oil on Masonite, 19 1/2 x 16 1/8 in. Formerly from the Collection of Janice Biala and Alain ‘Daniel’ Brustlein

Biala Paints a Picture: Summers in Spoleto

Biala (1903-2000) “Open Window: Spolète,” (1965-1968), oil on canvas, 63 3/4 x 44 3/4 in (161.9 x 113.7 cm) Photo Roz Akin

During the summers of 1965-1968, Biala attended the Festival dei Due Mondi in Spoleto. Her stay inspired several paintings and works on paper. Jason Andrew, Director of the Estate of Janice Biala, takes a took at one painting above all which celebrates Biala’s love, friendship, and appreciation of Henri Matisse.

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) “Open Window, Collioure,” 1905, oil on canvas, 21 3/4 x 18 1/8 in (55.25 x 46.04 cm) Collection National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney (1998.74.7)

Biala discovered for the first time the works of Matisse when the Brooklyn Museum opened an exhibition of French painting in the spring of 1921. It was a lasting and profound experience, one after which both Biala and her older brother Jack Tworkov decided to dedicate their lives to becoming artists. Tworkov said he “never forgot the impact of Cézanne, whose ‘anxieties and difficulties’ came to mean more to him than Matisse’s liberty and sophistication.” Biala on the other hand, though drawn to Cézanne’s structured compositions, would come to assimilate Matisse’s color and sensibility.

Biala first met Matisse during the decade of the 1930s by way of introduction through her lover and companion, the English novelist Ford Madox Ford. Biala would meet Matisse again visiting him in early 1954. Upon hearing of the death of the artist, Biala wrote that she “always had Matisse in my belly.”

Widely described as an icon of early modernism, Matisse’s small but explosive work titled Open Window, Collioure (1905), is heralded as one of the most important early paintings in the style of les Fauves.

Like Matisse’s Open Window, Biala’s painting belies an optical and conceptual complexity in which conventional representation is subordinated throughout by other pictorial concerns. Both paintings offer a vantage point upon a vantage point as the view moves from the interior of a room, to the open window, to the view point of the landscape beyond. In the case of Matisse, he offers the view of Collioure and the densely packed view of boats rocking on the French Mediterranean coast. For Biala, she offers a view of Spoleto the mountainous city in Umbria, Italy, which at the time had been reinvented by the summer Festival dei Due Mondi.

Biala first traveled to Spoleto in the summer of 1965 at the invitation of her friend the “the doyenne of international culture,” Priscilla Morgan, who at the time was the associate director of the beloved festival. Morgan is credited with bringing about a renaissance to the festival extending invitations to other artists, Isamu Noguchi, Willem de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller and musicians Philip Glass, Lukas Foss, and Charles Wadsworth among others.

Biala painted Spolète over three years likely taking sketches back to her Paris studio in the 7th arrondissement made from her summer visits. Subtly incorporating a series of variations on variations, this painting is Biala’s perfect assimilation of both the School of Paris and the New York School of Abstract Expressionism.

This historic work is now available at Berry Campbell.