Article: Janice Biala’s epochal studio via Two Coats of Paint

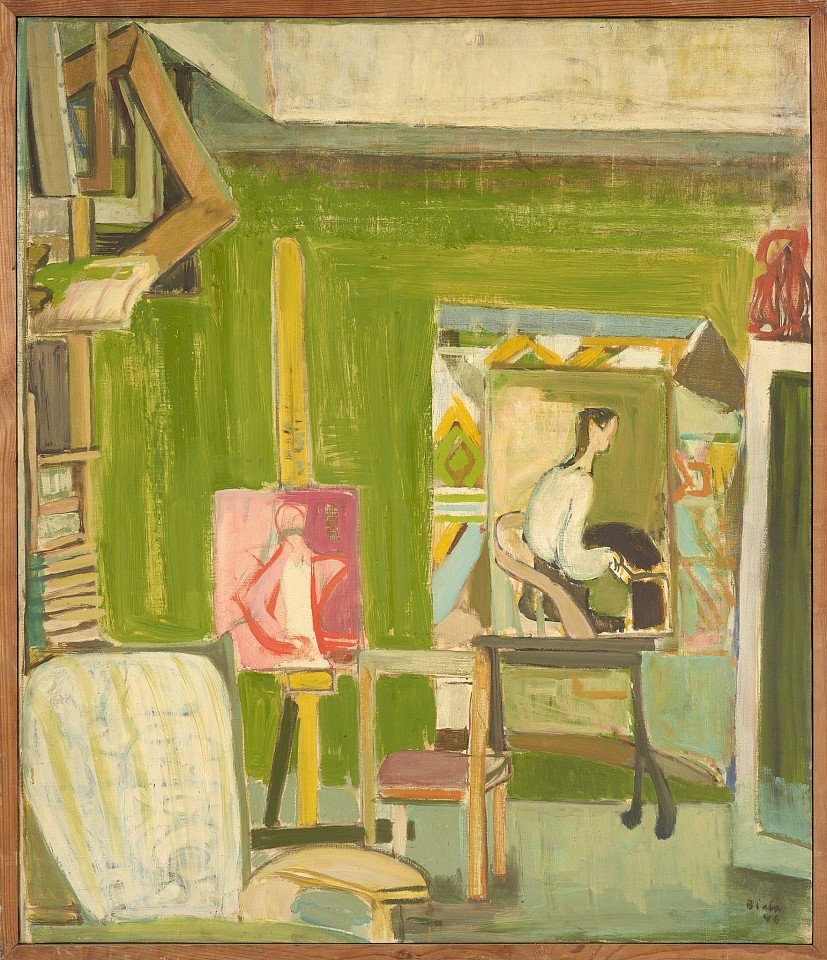

Janice Biala, The Studio, 1946, oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 22 1/2 inches

Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson

Published at Two Coats of Paint

April 6, 2024

A striking feature of the paintings and works on paper of Janice Biala (1903–2000), now on view at Berry Campbell in a show craftily curated by Jason Andrew, is their seamless reconciliation of civilizational clutter and spatial order. Fixing that notion is the earliest painting, The Studio (1946), arraying the artist’s active workspace and establishing her intent to embrace the world through it. (Coincidentally, Vera Iliatova’s “The Drawing Room” at Nathalie Karg gamely recaptures and updates kindred impulses.) Biala’s work here, spanning the immediate postwar period almost to the end of the Cold War and blending the New York School and the School of Paris – she lived in both cities – also bears the considerable weight of twentieth-century history, art and otherwise, with extraordinary grace and weightless cohesion, free of the strain of obvious contrivance.

Façade Blanche (White Facade), painted in 1948, depicts the physical strata of a Paris neighborhood with both due attention to detail and variegation and an implicit emphasis on the calmly agreeable organization of the visible environment, which is pointedly unoccupied. When Biala goes inside, as with Nature Morte à la Table (1948) and White Still Life (1951), she apprehends the material incidents of private life from a distinct remove, according them equal perspectival weight in cool tones that impart a sense of secure refuge within humanity’s sprawl and struggle. Even figures are absorbed into their inanimate surroundings. Jeune fille en rose, assise (Young girl in pink, sitting) is a moderate example, Two Young Girls (Hermine and Helen) a more extreme one verging on abstraction. The idea, it seems, is not the world’s erasure or engulfment but rather its harmonious accommodation of individuals, whatever their identities.

The trappings of Biala’s work are bohemian, not bourgeois, and it has a proletarian undercurrent. In Chevet de Notre Dame et l’ile St. Louis, 1949, the iconic church is iconoclastically painted from the rear, now a passive source of cultural comfort rather than an imposing summoning of faith or awe. Le Louvre (1948) is similarly down-to-earth, spied from the vantage of the Left Bank and settling humbly on the museum’s rooftop. Perhaps unsurprisingly, pieces from the mid to late 1950s, especially collages – see Violincelliste, Blue Parrot, and Untitled (Nature Morte) – are more abstract and suggestively gestural. Two drawings from the sixties – The Bather (Dana) and Study for “Blue Kitchen” – sunnily embrace the counterculture and 1960s modernism, respectively. Vaulting forward to the 1970s, the celebrated triptych Les Fleurs, isolating vases of flowers from separate perspectives, and Brown Interior with Rosine, presenting a woman sitting in drab comfort, assume a more austere, subdued, and regimented cast, perhaps a nod to the exigencies of age and the compulsion of preservation – or to fading glory.

It’s not too outlandish to say that Biala herself encapsulated the twentieth century, having lived 97 of its 100 years and tackled her vocation with versatility and virtuosity to match its historic eventfulness. She and her family – including her older brother, Abstract Expressionist painter Jack Tworkov – arrived in New York from Poland in 1913 and first lived in the tenements of the Lower East Side, which presumably attuned her early on to the tension between population and space. To distinguish herself from Jack, she took as her surname the name of the Polish town of her birth. She was the last romantic partner of the English novelist Ford Madox Ford, author of Parade’s End, a noted tetralogy on the First World War. After his death in 1939, Biala, at personal risk, extracted his manuscripts from Paris as the Nazis bore down. She experienced and absorbed the alternating currents of history, and on this score the two paintings on display from the 1980s seem telling in their divergence. Homage to Piero della Francesca is bright, busy, and elegiac – aptly enough, towards a Renaissance painter known for both his humanism and his geometric sense of order – while Black Still Life with Artichokes is contrapuntally dark, spare, and foreboding. From the studio, Biala perceived, as great artists often do, the promise and the peril of her time.

“Janice Biala: Paintings, 1946–1986,” Berry Campbell, 524 West 26th Street, New York, NY. Through April 13, 2024.

Article: How Artist Biala Left Her Mark on 20th-Century Modernism via Artnet

Janice Biala, Untitled (Orange Interior) (1967)

Published at Artnet

March 21, 2024

Every month, hundreds of galleries add newly available works by thousands of artists to the Artnet Gallery Network—and every week, we shine a spotlight on one artist or exhibition you should know. Check out what we have in store, and inquire for more with one simple click.

What You Need to Know: Presented by Berry Campbell, New York, in collaboration with the Estate of Janice Biala, “Biala: Paintings, 1946–1986” brings together more than 30 paintings—the largest showing of the late artist’s work in the city to date. The exhibition further marks the very first time many of the paintings are on view to the public. Accompanying the exhibition is a fully illustrated 100-page catalogue, featuring an essay by Manager and Curator of the Estate of Janice Biala, Jason Andrew, and an introduction by bestselling author Mary Gabriel, who also wrote Ninth Street Women (2018). “Biala: Paintings, 1946–1986” opens Thursday, March 21, and will be on view through April 13, 2024.

About the Artist: Janice Biala (1903–2000), born Schenehaia Tworkovska, maintained a unique practice that closely followed—and pioneered—the ideas and trends of 20th century transatlantic Modernism. Originally from the small city of Biała, Podlaska in the Russian occupied Kingdom of Poland, she immigrated to New York City in 1913. To assimilate, her parents changed her name to Janice; she later reclaimed the name of her birthplace, Biala, as her surname, and at the suggestion of artist William Zorach went by Biala as a mononym.

Developing a desire to become an artist at a young age, she went on to take courses at the National Academy of Design, the Art Student’s League, and trained under artists such as Charles Hawthorne and Edwin Dickinson. In 1930, she travelled to Paris, where she met and fell in love with English novelist Ford Madox Ford, who introduced her to many influential figures within the French art scene, including Gertrude Stein, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, to name a few. Following Ford’s death in 1939, and with the rising threat of Nazi invasion, she returned to New York.

Back in the city, she became a recognizable figure within the burgeoning avant-garde arts scene and one of the few women engaging with Abstract Expressionism. In 1955, the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired one of her works, the first institution to do so. Ultimately, her career spanned seven decades and two capitals of the art world, and is recognized as an imperative facet to the development of Modernism.

Why We Like It: Moving seemingly intuitively between abstraction and representation, the synthesis of elements from both the School of Paris and New York Abstract Expressionism is unmistakable. The exhibition of her work at Berry Campbell, which includes paintings dated from across a 40-year period, lets viewers visually accompany Biala through the trajectory of her artistic experiments and evolution. In early works like The Studio (1946), perspectival space is distorted but still very much discernable, offering a charming view into a green studio room. In works such as Red Interior with Child (1956) from a decade later, the depiction of space is largely relegated to the title of the painting, and the composition is overrun with swaths of vibrant pigment, with only the suggestion of a child on the right edge of the canvas. Her investigations into abstraction also didn’t stop with paint, as Casoar (The Cassowary) (1957) shows, made from collage comprised of torn paper with oil on canvas. The show is a testament to Biala being poised for not only reappraisal within the context of the art historical canon, but her singular contribution to the narrative and development of 20th-century Modernism.

Article: "Peintresses en France: Janice Biala" via DIACRITIK

Biala working on canvas at the apartment of the critic Harold Rosenberg, with the painting “Two Young Girls,” c.1953. Courtesy Estate of Janice Biala. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Paintresses in France (15) : Janice Biala (1903-2000), Painting for Country

by Carine Chichereau

Published in DIACRITIK

December 15, 2022

The following is the complete English version translated by Noémie Jennifer Bonnet from the original with permission from the author and DIACRITIK. Click here for the original article in French.

Biala in her Paris apartment, 1947. Photo: Henri Cartier-Bresson © Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos

Outside of painting, Janice Biala had two great loves in her life: France, and the writer Ford Madox Ford. Born in a large garrison town in Poland, then under tsarist Russian rule, she expanded her horizons at a young age, discovering New York and the bohemian Greenwich Village, Provincetown back when it was still a village of artists and fishermen, and the buzzing Parisian scene of the interwar period, where she met Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Piet Mondrian, among others. After fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe, she championed Willem de Kooning’s work, participated in the founding of abstract expressionism in New York alongside the biggest artists of the era, and eventually settled back in France, like Joan Mitchell and Shirley Jaffe, where she became part of the so-called “School of Paris.” Her life ended as the twentieth century came to a close.

Biala is a bridge between Europe and America, between modernism and abstraction. Biala signifies eight decades of artistic practice covering nearly the entire 20th century, yet whose inimitable style is instantly recognizable. Biala is a paintress with a steel will, who never ceased to fight and adapt to difficult circumstances. She went so far as to change her name and nationality, while never renouncing her identity, and in the end she found her place among the greats of her time, despite being born female and Jewish in the empire of the tsars.

Biala’s story begins at the close of the nineteenth century, and ends at the threshold of the twenty-first. Schenehaia Tworkovska was born September 11, 1903 in Biala Podlaska, a largely Jewish garrison town that held great importance to the Russian empire that ruled Poland at the time. Her father, a tailor named Hyman Tworkovsky, already had many children. Following the death of his first wife, he marries Esther, who gives birth to Yakov in 1900 and Schenehaia in 1903. In 1910, likely hoping for a better future for himself and his family, Hyman Tworkovsky decides to emigrate to the United States, at first taking only with him the children from his first marriage, who are all approaching adulthood. A cousin named Bernstein serves as a “sponsor” for the cause of “family reunification.” However, for this to work, a shared last name is a requirement: thus Hyman Tworkovsky becomes Herman Bernstein.

“Biala’s life is a novel, a theater of all the upheavals of the 20th century.”

“White Still Life,” 1951, oil on canvas, (66 x 91.4 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

What kind of childhood did Schenehaia lead, alone with her brother and mother in a military town, in the early years of the twentieth century before everything exploded? Did children draw back then? Did the absence of their father and siblings cause them to suffer? How did they cope with the uprooting of their lives, three years later, and the long one-way voyage to a new land? During this time, their father has been able to establish his business as a tailor in Manhattan, and he brings them over as soon as he can. At the time, European migrants arriving at Ellis Island by the millions, many of them hailing from Eastern Europe, many of them Jews who feared persecution. What are the odds of a ten year-old girl born into poverty becoming an internationally recognized artist in a foreign land that speaks a foreign language?

After a transatlantic voyage that, for a child, must have been as terrifying as it was exciting, she arrives in New York on September 26, 1913. I can easily envision a Biala painting with an unadorned view of the port, in pinkish hues, a hazy statue of Liberty in the horizon, the symbol of possibility. Is their future rosy? Not at first.

“L’atelier du Marché Saint-Honoré,” 1982, oil on canvas, (96.5 x 144.8 cm), private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

As soon as they set foot in America, Schenehaia and Yakov Tworkovsky are reborn as Janice and Jack Bernstein. The entire family piles inside the father’s tailor shop, located in tenement housing for the poor. At the time, the Lower East Side was teeming with destitute immigrants who would stop at nothing to reinvent themselves and build a new life. Janice and Jack are no different: both siblings possess that extraordinary adaptive ability to transform every obstacle into an opportunity, every challenge into possibility. A fruitful rivalry quickly develops between them, and they will remain close throughout their lives, primarily thanks to a regular correspondence. We know very little of their youth, but one can imagine them in school working side by side, learning English,taking on the occasional odd job. One can imagine the cultural and linguistic shock they must have felt with nothing familiar in sight, save for a few family members.

They must have adapted quickly to their new environment, because, in their late adolescence, seeking something more than their parents could offer, Jack brings his sister along to settle in Greenwich Village, the hub for artists and bohemia since 1850. Together, they decide to take back their given family name, minus its last syllable. They become known as Janice and Jack Tworkov. He attends Columbia University, aspiring to become a writer or journalist, but everything changes one spring day in 1921. Epiphany strikes.

On view at the Brooklyn Museum at that time was the first exhibition in the United States of the paintings of Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse. For Janice and Jack, it’s a shock to the system. He is enchanted by Cézanne; she is enthralled by Matisse. She is 18 years old, and sweeps her brother toward painting. From then on, she knows what she wants and enrolls (with her brother) in the National Academy of Design, grabbing every odd job possible in order to finance her studies—working in sales at Macy’s, or as an employee of the telegraph company Western Union. Having discovered the paintings of Edwin Dickinson through a winter exhibition at the National Academy of Design, in 1923, Janice persuades Jack to go spend the whole summer in Provincetown, and they hitchhike the whole way there.

Janice’s meeting with Dickinson would prove foundational to her development. One need only look at his paintings to understand the lineage: a denuded version of reality; pared-down landscapes; flat, subtle tones circumscribing space; and colors that hold together the composition. Dickinson teaches his apprentice to focus on essentials, to go beyond what she sees in order to extract an abstract vision in two dimensions. He insists that color harmony is more important than the representation of subject. For him, the starting point of a painting is a dab of color, or rather two: “Two dabs of color on the same plane, which is of course necessary because you can’t have just one color. They all exist in relation to a common harmony.”

Biala is a colorist. And her usage of color—assimilated very quickly at Edwin Dickinson’s side, as far from realism as it is from sentimentalism—makes her a modernist like her mentor. In 1937, during a lecture to the Colony Club at Oberlin College, she goes even further: “The very first spot of paint that you put on your canvas sets the note for everything that must follow. Just as in writing a novel, and no doubt in music and the other arts, every word you write must lead up to your climax, and no word or phrase must be there just because you happen to like it, so each spot of paint in your picture must lead up to some definite movement and must connect with every other spot of paint in the picture. Because red is not red by itself; its full quality of redness only becomes apparent when it has green beside it or the full quality of green is brought out only when it has purple beside it and so forth. Then against the color you play your forms, lines and texture.”

Jack is taken with life in Provincetown, but Janice decides to return to the bohemian society of the Greenwich Village. It is Provincetown, however, that hosts her first group exhibition in 1927. By the end of the 1920s, she is gaining traction and exhibiting in galleries like G.R.D. Studio, which birthed the careers of many young artists of the time. In parallel, she remains active in the artist colonies of Woodstock and Provincetown, becoming friends with Blanche Lazzell, Dorothy Loeb, and William Zorach, and keeping close ties with Edwin Dickinson. The stock crisis of 1929 leaves her in dire straits: galleries are no longer selling and unemployment hits a record high. In the midst of all this, she marries the painter Lee Gatch on a whim.

She writes then, “If I ever get a hundred dollars, I’m going to Europe and stay there.” In April 1930, her friend, the poet Eileen Lake, invites her to Paris. The stars align as two wealthy art patrons offer to pay for her trip. Around the same time, she decides to follow the advice of the painter William Zorach, and changes her name again. She writes to Jack, “I decided to change my name in order not to be confused with you [...] My name is now Biala. It’s not a bad idea if I want to continue to paint.” Amid all these changes, she comes to understand that painting is the only thing she knows how to do. Sadly, very few works from this period have survived.

“Snow in the Courtyard,” 1976, oil on canvas (119.4 x 120.7 cm) Private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“The Violin,” 1924, oil on canvas, (55.9 x 53.3 cm) Collection of the City of Provincetown. Donation of Jay and Pat Saffrom. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“The very first spot of paint that you put on your canvas sets the note for everything that must follow.”–Biala, 1937

“Yellow Still Life,” 1955, oil on canvas (162.6 x 132.1 cm). Private collection, France. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In hindsight, the year 1930 truly appears to be a decisive moment in Biala’s career. At 27 years of age, she is a strong, opinionated free thinker who decides to take her existence in her own hands, carrying her past experiences and artistic training in tow. Shortly after obtaining American citizenship, she leaves the United States and liberates herself from the destiny chosen for her by her father. Instead she invests fully in her painting; she carves some space away from a talented brother who might easily overshadow her; and she severs a conjugal knot tied too soon, clearing a path towards what will be her greatest love story. Simply put, she reinvents herself.

At this time, Janice Biala’s favorite book is The Three Musketeers. Later on, she will say it was because of the Porthos character that she became an artist. Surely it is this literary sensibility that leads her, shortly after her arrival in Paris, to accompany her friend Eileen Lake to Ford Madox Ford’s weekly Thursday salon. She is dying to meet Ezra Pound, who is scheduled to be there that day but never shows up. Biala, disappointed, ends up sitting next to the host, whose accomplishments she ignores. Yet the 56 year-old writer happens to be one of the most successful English authors of the time. He is an absolute workaholic who has published over sixty books, founded two literary magazines, and also works as a critic and editor—the first to publish James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. He also happens to be quite the ladies’ man, having racked up a history of consecutive relationships with one eminent woman after another, many of them writers and artists, including none other than Jean Rhys. The “long passionate dialogue” (Biala’s words) that they began on May 1, 1930 would continue until June 1939, upon Ford’s death.

All of Ford Madox Ford’s friends can plainly see that day that he is completely smitten with the young paintress, who exhibits great maturity despite her youth. After all other guests leave, Ford invites Biala and Eileen Lake to go out to eat, and they go dancing until dawn. Janice Biala and Ford Madox Ford meet a number of times in the following days, becoming inseparable after only a month. In letters to her brother, Biala does not mention Ford until their engagement four months later. At his side, she is directly immersed in the Parisian literary and artistic scene. Having lived in France since 1922, Ford knows absolutely everyone: members of the literary scene like Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound and James Joyce, as well as avant-garde artists like Henri Matisse, Constantin Brancusi, Juan Gris and Pablo Picasso, whom Ford regards as the greatest among them. Paris is still the center of the art world then, and artists of all nationalities train there. For a young painter from across the Atlantic, it’s a dream come true.

Ford Madox Ford knows about art, and his experience allows him to build up his partner’s confidence. In 1931, in a letter to her brother, she writes, “For the first time in my life I’m convinced that I am really an artist.” Like Edwin Dickinson, Ford encourages her to foster her own aesthetic vision, while experimenting freely and seeking the poetic essence of things, rather than remaining loyal to their appearance. Indeed, when one thinks about Janice Biala’s paintings, what comes to mind are those subtle colors with great attention to nuance: a simplified version of the world, as though she wanted us to see images stripped of all that is superficial, retaining only the essence of things. Whether a landscape, an interior scene or a still life, her canvases consistently conjure a sense of fluidity that holds realism at a distance, though one can still recognize the objects that are presented. It is the singular vision of a painter transcending reality. Never forget this quote from Biala, which captures her artistic quest so well: “I’ve always had Matisse in my belly.”

One might easily assume that the relationship between the young, petite paintress and the tall, corpulent writer, thirty years her senior, would have been unbalanced, and yet the opposite is true. For nearly ten years, they share everything: he brings his experience, introduces her to the greatest artists and writers in Europe, even organizes her first solo show in New York in 1935 at the Georgette Passedoit gallery. She brings her relentless energy and breathes in him new inspiration, helps him organize his work, handles his contracts (a weakness of his), even illustrates several of his books. Both are free spirits, focused on their artistic endeavors, uninterested in societal conventions. Money and social status hold no importance; only art counts (including the art of good living—never deprive yourself of good food and drink). So describes their bohemian life in Paris, Toulon, and later the United States. Ford writes; Biala paints.

In their early years together, Janice Biala and Ford Madox Ford travel to Germany and Italy. Together they witness the rise of fascism, which shakes them to their core. For Biala, the persecution of Jewish communities echoes the experiences of her father. As soon as Hitler assumes power, she convinces Ford to write articles in the British press denouncing the situation faced by Jews in Germany. She writes in a letter that it represents a return to the Middle Ages. She remains keenly aware of current events and a sharp critic, decrying the absence of true political efforts to stop Hitler. She is also not shy about reprimanding Ezra Pound for his fascist sympathies. In 1933, she writes to her brother: “All of the world’s cruelty and misery stem from a lack of imagination. Thus I believe that liberating our imaginations can save us, and only art can do this.” It is hard to imagine a more fervent defense of the value of art.

Simultaneously, her career gains traction. In 1932, she is invited to participate in an important artistic project titled “1940,” held at the Porte de Versailles exhibition center. It is her first large group exhibition, with four of her works on view. Organized by the Association Artistique, the exhibition aims to push the envelope, and includes many abstract works. Female artists hailing from different European countries are invited to participate; other than Biala, Alexander Calder is the only American artist in the show. The exhibition includes Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Francis Picabia and Piet Mondrian. In 1938 and 1939, Biala is offered a solo exhibition at Gallery Zak in Paris. Towards the end of the 1930s, she travels frequently to the U.S. with Ford Madox Ford, as his fame leads to numerous writer’s residencies and professorships. This allows Biala to maintain ties to the American art world and exhibit in several U.S. cities. Sadly, upon their return to France, in June 1939, on a vessel headed for Normandy, Ford falls terribly ill and has to be hospitalized in Deauville. He dies on June 26, leaving Biala devastated. Quickly, she commits to keeping her beloved’s literary legacy alive. Many of their works were stored in the house they occupied for years near Toulon. From this point on, she sets two goals for herself: to paint, and to preserve Ford Madox Ford’s legacy. War breaks out, and the world falls apart at a moment she is herself in pieces. In a letter, she calls it a “war against the spirit.” Despite a lack of funds, she manages to return to Toulon, where she packs up six or seven canvases along with Ford’s manuscripts and his precious correspondence. She barely manages to board the last ship to the United States, and by mid-November 1939, she finds herself back in New York, where a new life awaits her.

“Portrait of the writer (Ford Madox Ford)” 1938, oil on canvas (81.3 x 66 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“The Flower Pots” 1985, oil on canvas (132.1 x 96.5 cm). Private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

« Porte de l’Umilta (Pont de l’humilité) », 1985, oil on canvas (diptych), (195.6 x 261.6 cm), Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Back in the United States, she reunites with Edwin Dickinson in Provincetown, and most importantly with her brother Jack Tworkov, who has since become a well-known painter with many connections. Thanks to him, she finds a place in the New York scene, slated to replace Paris as the center of the art world. In 1941, she begins exhibiting with the Bignou Gallery. By this point, however, Janice Biala is a broken woman who has lost her greatest love, and been forced out of the country she had chosen to build a life. In spite of all this, she continues to paint non-stop; it is likely the only thing keeping her alive. She goes for frequent walks with a sketchbook at her side. One day, while drawing on the beach at Coney Island, accompanied only by a bottle of whiskey, a large, fairly attractive man taps her on the shoulder. His name is Daniel Brustlein, soon-to-be her second biggest relationship.

Daniel Brustlein was born in Mulhouse in 1904. He arrived in the United States at the age of twenty after attending the Beaux-arts school in Geneva. At the time of their meeting, he is a well-known illustrator for the New Yorker, signing his illustrations as “Alain.” The two had in fact already met at a party in New York a few years earlier. This chance encounter at Coney Island—another scene that would make a good Biala painting—marks the beginning of a story that would last 55 years. They marry on July 11, 1942. Alain is at the peak of his career; his drawings have just garnered him several prestigious prizes. And Janice Biala, by then a well-known painter who never really stopped exhibiting in New York, inspires her new spouse to delve more deeply into his own painting.

Her brother, Jack Tworkov, is responsible for her introduction to Willem de Kooning. Two months later Brustlein takes her for a studio visit on her birthday, and gifts her one of the artist’s paintings. They forge a friendship. Brustlein and Biala begin collecting de Kooning’s paintings, take care of him when he gets sick, even organize a reception for his marriage to the painter Elaine Fried the following year, as he lacks the funds to do so himself. Eventually, Janice Biala manages to convince her gallerist to exhibit her friend’s paintings. She is now an influential artist, one of the few women who saw enough success to find themselves included, in 1946, in a group show at the Bignou Gallery with Giorgio De Chirico, Raoul Dufy, Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault and Chaïm Soutine.

“All of the world’s cruelty and misery stem from a lack of imagination. Thus I believe that liberating our imaginations can save us, and only art can do this.” –Biala, 1933

“Green Tree,” 1958, oil on canvas (162.6 x 132.1 cm), Private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

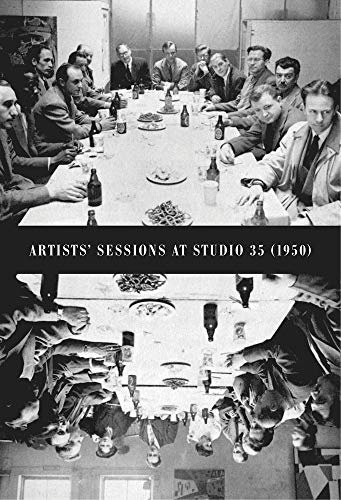

It is around this time that a disparate group of artists begins to form in New York, united by one common goal: to sever their ties with movements past—cubism, surrealism, futurism—and create something new. It is a veritable creative whirlwind—a response, certainly to the dark years of the war. In 1948, Biala participates in three days of discussion aimed at structuring this new movement, with the likes of Louise Bourgeois, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, and Barnett Newman. Motherwell pitches three possible designations to his colleagues: Abstract Expressionism, Abstract Symbolism, and Abstract Objectionism.An entire galaxy of artists begins to orbit around what would finally be dubbed “abstract expressionism,” even though many of them could neither be classified as abstract or expressionist. Two years later, on April 21st and 23rd, 1950, Janice Biala is again one of the few women, along with Louise Bourgeois and Hedda Sterne, to participate in a private meeting now known as “Artists Session at Studio 35,” essentially the birthplace of the abstract movement in New York. (One should not forget that this abstract movement was dominated by men both in the U.S. and in France, with only a few women admitted entry, but always kept in the background.)

From 1950 to 1965, Janice Biala traverses a period in her work focused on abstraction. She pushes to its limit a process that was already reductive, distilling reality to bare essentials. Nonetheless, most of her canvases maintain a connection to representation, albeit a tenuous one, very much unlike the Action Painters of the time, for whom gesture and the act of painting are as important as the resulting work. In contrast, Biala’s starting point is always reality, even though it is stripped, through the lens of her imagination, of all the concrete markers that anchor it to actual reality, leaving instead a kind of final essence.

“The Beach,” 1958, oil on canvas (124.5 x 83.8 cm) Art Enterprises, Ltd, Chicago, IL. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

During this period, she keeps one foot in New York and the other in Paris. In 1947, Biala and Brustlein board a ship destined for France. They befriend Henri Cartier-Bresson aboard the vessel, and the photographer agrees to rent them his studio in Paris. In a letter to Jack Tworkov dated December 3, 1947, she writes, “I’ve found all I ever wanted in France. Heaven doesn’t interest me if it doesn’t look like France.” Forty years later, in 1989, while reminiscing about her experiences in Paris and New York in an interview with the New York Times journalist Michael Brenson, she is quoted as saying, “I fell in love with France. In some ways, it reminded me of the place I was born in. And when I came to France I felt as if I had come home. I smelled the same smells of bread baking and dogs going around in a very busy way, you know, as if they knew what they were about. It really was extraordinarily human. I hadn't known when I was in New York that the skyscrapers were weighing on me, and I felt as if they had suddenly fallen off. [...] There's a certain sweetness in life here which I think is very much lacking in a city like New York.” Seven years have passed since her escape from Nazi invasion, seven years during which she has rebuilt her life, remarried, and advanced her career. She regularly exhibits in New York, and the same is true of Paris as of 1948, at the Jeanne Bucher gallery and the Salon des Surindépendants.

Upon her arrival in France, she carries the halo of the New York school’s latest current: she is in the perfect position to spread the gospel to French artists, and everyone wants a piece. She reunites with old friends, including Matisse and Picasso. Conversely, all of the American artists visiting Paris pay her a visit as soon as they arrive, hoping for an introduction to the Parisian scene: it is a nonstop parade that she laments in her letters. Numerous are the artists looking to settle in Paris back then, such as Ellsworth Kelly, and notably, Shirley Jaffe in 1949, then Joan Mitchell in 1955.

Did Paris offer an environment more favorable to female painters in the second half of the 20th century? To hear Joan Mitchell in a 1989 interview for that same article in The New York Times, one would certainly think so: “To me, New York is very male [...] Paris is female [...] In France, they've always said my work is violent gestural painting. In New York, they've said it's decoration. On both sides, they say it's female.” All three—Biala, Jaffe and Mitchell—are driven by color, and Mitchell adds, “There are no colorists in New York.”

“Her whole life, Biala had to fight to exist—as a woman, as a Jew, as an immigrant, and as a painter who wanted her talent to be recognized.”

“Two Young Girls (Hermine and Helen)”, 1953, oil on canvas (152.4 x 119.4 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“Invalides II,” circa 1967, oil on canvas (101.6 x 101.6 cm), private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

The 1950s are a period of both deepening development and dispersion for Biala. I say dispersion because, although they want to live in France, Biala and Brustlein cannot risk losing their American citizenship. During this somber period marked by McCarthyism and paranoia, they are legally required to return to the U.S. every two years, and remain there for a period of time in order to retain their citizenship. Every two years, they must move from one continent to the other. The painter Hermine Ford, daughter of Jack Tworkov, then a teenager, describes this period of her family history thus: “My entire childhood was characterized by their comings and goings. [...] It was wonderful when they were here. But my sister Helen and I were very scared of [Biala] when we were little. She was a tough cookie. [...] Once we got older, we loved her, she was the last survivor of the four, and Helen and I were completely devoted to her. She didn’t have kids, so she kind of appropriated her nieces, and she was such a hypocrite with us; she yelled at us because we sat with our legs too far apart, and would tell us ‘Young girls in Paris don’t sit like that.’ Meanwhile I’ve rarely ever seen her in a dress; she was a real tomboy. She was tough as nails. You had to be if you wanted to be an artist at the time. She presented herself as the woman who chain-smoked, cursed, and sat down however she liked.” Nonetheless, Biala was a very elegant woman, who had her shirts tailored in silk fabrics brought back from India, who left behind a trail of the perfume l’Heure Bleue by Guerlain, and who, according to many testimonials, remained attractive even in her old age.

“Cuisine rose,” 1969, oil on canvas (88.9 x 115.6 cm) private collection. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In 1960, Janice Biala and Daniel Brustlein buy a house at 8, rue du Général Bertrand in the 7th arrondissement, finally settling for good in Paris. Their home is a former stable facing the interior courtyard of a building. They move in, build out each of their studios, and quickly the location itself becomes an endless pool of inspiration for Biala. She paints everything under every angle imaginable: the cat, the kitchen, the courtyard…The city of Paris itself is also a continuous source of material. She frequently paints the outskirts of the Seine, the Louvre, Notre-Dame, as well as more anonymous Parisian façades. In her studio, she crushes natural pigments with a bit of linseed oil, then dilutes them with turpentine and lays them out on a glass palette. She begins by deconstructing reality in her head, outlining shapes and volumes in order to recreate them on the canvas. In order to combat blank canvas syndrome, she quickly adds a few dabs of paint on the empty surface. The first stages of her compositions feature very few filled-in areas; she tries things out, erases when necessary with a palette knife, a razor blade, or sandpaper. She does not work from precise, finalized preparatory sketches, but continues to sketch while working on her painting, trying out ideas in her sketchbook until she is satisfied and can translate them onto canvas. If she encounters a problem midway, she goes back to drawing until she finds a solution.

In 1962, the Beaux-Arts Museum of Rennes becomes the first French museum to offer her an exhibition. In 1965, the Biala-Brustlein couple’s first shared exhibition is presented by the Beaux-Arts Museum of Paris. A long series of such exhibitions follows. The paintings of Daniel Brustlein (known as a painter’s painter) show an evident link with Biala’s work. One can easily picture how the two worked alongside each other, and they even collaborate on several projects outside of painting, among them children’s books. During this period, they live a bohemian life reminiscent of the pre-war years: friends show up, and they go out and party. Biala becomes friends with Shirley Jaffe, Joan Mitchell, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, and Alberto Giacometti.

Janice Biala continues to paint and exhibit indefatigably until the end of her days. She participates most frequently in group exhibitions in the fifties and sixties, both in France and the United States, as well as Canada, Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, Israel and Spain. She shows frequently alongside Joan Mitchell, Vera Pagava and Maria Helena Vieira da Silva. In 1981, the critic Hilton Kramer writes in The New York Times: “Whether she draws her subjects from Venice or Provincetown or the interior of her studio in Paris, Biala is a painter of remarkable powers. The structure of her pictures often looks quite simple, but it usually turns out to be ''simple'' in the way that paintings by Marquet and certain schools of Japanese painting can be called simple. Which is to say, not simple at all. The difficulty and complexity have been refined into lean, direct gestures and a lyrical, concentrated economy of form. Especially in her landscape and seascape paintings, Biala has a wonderful sense of place and a flawless eye for the way place is defined by light.” The critic signs off by saying it is Biala’s best exhibition to date.

Throughout her career, she has had back-to-back solo exhibitions in galleries, sometimes even in museums, at least one per year. In 1990, at a remarkably vivacious ninety years of age, she changes galleries, and continues to exhibit almost yearly at the Kouros Gallery. Following the death of Daniel Brustlein on July 14, 1996, her productivity decreases considerably, and her last exhibition takes place in 1999 in New York. She dies at home in Paris on September 24, 2000.

“Pink Venice,” 1983, oil on canvas (132.1 x 195.6 cm) Current location unknown. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

“Le Chat aux bords verts (Ebony),” 1990, oil on canvas (81.3 x 81.3 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Her whole life, Janice Biala had to fight to exist—as a woman, as a Jew, as an immigrant, and as a painter who wanted her talent to be recognized. At the very beginning of her career, after having changed names several times already, she chose one for herself, that of her birthplace: Biala. Art is her country, and she says it best: “I'm Jewish. I was born in a country where it was better not to be Jewish. Wherever you go, you're in a sense a foreigner. I've always had the feeling that I belong where my easel is.” And yet it is difficult not to see in this choice an homage to her roots. Polish, American, French…Biala was all of these things at once.

It is difficult to imagine today all of the obstacles that this young, courageous, ambitious woman had to overcome. The question of her name is not insignificant: female artists tended to change names, often reluctantly, upon marriage for example. For a long time, women have not had control over their identity, which was handed down to them by a man through lineage or marriage. Janice Biala had understood this when she first chose to break with family tradition, then break away from a brother with the same last name, whose proximity risked overshadowing her success. She never took any of her husband’s names. During the 1940 exhibition in Paris, in 1932, a New York Times critic referred to her as “Janice Ford Biala.” She expressed her outrage in a letter to her brother: “The damn fool had to give me the wrong name (I do not sign my work as Janice Ford Biala), but what hope is there when someone thinks one paints like a slow dance of joy or some such twaddle?”

In 1953, she wrote a letter to ArtNews following their publication of an article about her work: “No one has ever written an article about me in your paper without mentioning one of my dear husbands, and now, everyone knows my secret. I also have a brother!” Here she is protesting the relentless treatment of women as creatures who could not possibly exist without a man, who are destined to exist in the shadows of their fathers, husbands and brothers, as is the case at the time for Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning or, in France, Anna-Eva Bergman. This phenomenon is often not instigated by the men in these women’s lives, but perpetuated by critics, gallerists, and an entire art world firmly anchored in a patriarchy that cannot conceive that an artist might exist autonomously, without owing her talents to a man.

“Open Window,” circa 1964, oil on canvas, (116.8 x 88.3 cm) Collection of the Estate of Janice Biala, New York. © 2022 Estate of Janice Biala / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Today Janice Biala is a paintress whose name is not mentioned often, despite the amplitude of her talent and œuvre. It is possible that her division across two continents has not served her legacy well, as it is difficult to exercise considerable influence without a permanent anchor in a single place. Further, during her abstract period, as she is approaching the culmination of her artistic practice, her work falls well outside of contemporary trends, namely conceptual art. In this avant-garde milieu, painting is out of style, and figurative painting even more so—even Biala’s pared-down version.

Janice Biala is therefore an artist who deserves to be rediscovered and studied, not only for her work, but also for the influential role she held in the establishment of abstract expressionism in New York, as well as her presence at the heart of the School of Paris. Biala’s life is a novel, a theater of all the upheavals of the 20th century. The ultimate destiny of this Jewish tailor’s daughter, born in tsarist Russia, is so incredible that it is hard to believe that no one has optioned the rights for a book or a movie. Janice Biala is not only a great artist; she is an important figure of the 20th century whose struggles, willfulness, and resilience can serve as an example for women today.

I want to thank Jason Andrew, who manages the estate as well as the beautiful site dedicated to Janice Biala, and where one can find absolutely everything about her, including a chronology of her life, photos of her and her work, articles, online conferences, etc. I highly recommend paying the site a visit, if only to see more works by this great artist: janicebiala.org

END

Exhibition News (via Artful Daily): The Shape of Freedom: International Abstraction After 1945

The exhibition focuses on the two most important currents of abstraction following World War II: Abstract Expressionism in the United States and Art Informel in western Europe.

Janice Biala, Untitled (Still Life with Three Glasses), 1962. Oil and collage on canvas, 162,6 x 145,4 cm. Collection Richard and Karen Duffy, Chicago. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022 Image: McCormick Gallery, Chicago

Jackson Pollock, Composition No. 16, 1948. Oil on canvas 56,5 × 39,5 cm. Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

The role of the artist, of course, has always been that of image-maker. Different times require different images. ... To my mind certain so-called abstraction is not abstraction at all. On the contrary, it is the realism of our time. - Adolph Gottlieb, 1947

The Shape of Freedom: International Abstraction after 1945 is a major new traveling exhibition debuting at the Museum Barberini, in Potsdam, Germany, on June 4, 2022.

The exhibition focuses on the two most important currents of abstraction following World War II: Abstract Expressionism in the United States and Art Informel in western Europe. The Shape of Freedom is the first exhibition to explore this transatlantic dialogue in art from the mid-1940s to the end of the Cold War.

The show comprises around 100 works by over 50 artists including Sam Francis, Helen Frankenthaler, K. O. Götz, Georges Mathieu, Lee Krasner, Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Judit Reigl, and Clyfford Still. Works on loan come from over 30 international museums and private collections including the Kunstpalast Düsseldorf, the Tate Modern in London, the Museo nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

After its opening run in Potsdam, a version of the exhibition will travel to the Albertina modern in Vienna (opening October 15, 2022) and then the Munchmuseet in Oslo.

Ortrud Westheider, Director of the Museum Barberini, Potsdam, said, “The paintings in the exhibition bear witness to the tremendous longing for artistic freedom that emerged on both sides of the Atlantic after 1945. The Hasso Plattner Collection, with important works by Norman Bluhm, Joan Mitchell, and Sam Francis, served as our point of departure. The concept developed by our curator Daniel Zamani was so convincing that the Albertina modern in Vienna and the Munchmuseet in Oslo agreed to host the exhibition as well. I am delighted to see this European cooperation.”

World War II was a turning point in the development of modern painting. The presence of exiled European avant-garde artists in America transformed New York into a center of modernism that rivaled Paris and set new artistic standards. In the mid-1940s, a young generation of artists in both the United States and Europe turned their back on the dominant stylistic directions of the interwar years. Instead of figurative painting or geometric abstraction they embraced a gestural, expressive handling of form, color, and material—a radically experimental approach that transcended traditional conceptions of painting. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Hans Hofmann, and Joan Mitchell discovered an intersubjective form of expression in action painting, while the color field painting of Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, and Clyfford Still presented viewers with an overwhelming visual experience.

Review: Biala: Courage of Her Convictions

Edwin Dickinson Portrait of Biala, nee Janice Tworkov (1924) Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm) Private Collection, New York

by Xico Greenwald

Janice Tworkov (1903-2000) changed her name to Biala to differentiate herself from her older brother, Abstract Expressionist Jack Tworkov. The artist-siblings, Jewish immigrants from Poland raised on the Lower East Side, lived divergent lives.

An action painter, Jack Tworkov played a leading role in shifting the center of the art world from Paris to New York after World War II. Biala, on the other hand, moved to France during the interwar period, where she socialized with some of the leading writers and artists in Europe, including Picasso, Matisse, Gertrude Stein, Brancusi and Ezra Pound. There she embraced the modernist innovations of synthetic cubism, making quiet cityscapes and interiors that emit the gray light of Paris.

This Queens College retrospective opens with an arresting portrait of 21-year-old Biala by her teacher Edwin Dickinson. The darkly colored portrait is softly modeled with crisp contours; Biala’s gray eyes stare out in a confident, unflinching gaze.

Next to Dickinson’s portrait are several ink-on-paper illustrations for Ford Madox Ford’s “Great Trade Route,” published in 1937. Biala met Ford upon arriving in Paris in 1930 and the couple remained lovers until Ford’s death in 1939. Notable works from this period include dizzying paintings of bull fights, arena pictures alive with movement, and a roughly drawn portrait of Ford, with hash marks over rubbed graphite tones giving the writer’s head sculptural form.

But it is after World War II that Biala came into her own. In “White Façade,” 1950, the shuttered windows of Paris’ limestone buildings are abstracted into thinly painted olive and ochre rectangles. On the right edge of the canvas a tree’s foliage is also simplified into muted green geometry, as the blocky shapes and colors convey an overcast day.

“Nature Morte,” 1963, a tabletop scene, features loose strokes of black carving out a white tablecloth arrangement. The canvas presents a wonderful interplay of negative and positive shapes. In “Table Chargée,” 1963, Biala, working in collage, uses clusters of torn pieces of colored papers to roughly describe an interior.

In the 1980s and 90s Matisse’s influence on Biala seemed to grow as her paintings flatten and objects, including cups, fruits, books and even a cat, are isolated in fields of color.

Neither during her long life nor in the years since her death has Biala’s contribution to art history received the attention it deserves. Museum Director Amy H. Winter says “the politics of gender and style” and the fact that Biala “never fully embraced the mythic freedom and daring associated with abstract expressionism” left the painter “marginalized.” Making “intimate” artworks while living in Paris “rendered her ‘other.’” For Ms. Winter this overdue exhibition “serves as a tribute to artists who, like Biala, persist in remaining faithful to their personal vision.”

BIALA: Vision and Memory on view through October 26, 2013 at Godwin-Ternbach Museum, Queens College, CUNY, 405 Klaper Hall, 65-30 Kissena Boulevard, Flushing, NY, 718-997-4747, www.qc.cuny.edu/godwin_ternbach

Biala and Brustlein, a concurrent exhibition featuring works by Biala and her husband, cartoonist Daniel “Alain” Brustlein is on view through October 27, 2013, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, 724 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, 212-262-5050, www.tibordenagy.com

More information about Xico Greenwald’s work can be found at xicogreenwald.com

Review: Bohemian Rhapsody: Paintings by Janice Biala

Biala, “Vue despuis de la Giudecca,” 1985, Oil on canvas, 77 x 59 in.

December 13, 2007

One of the tangential intrigues of art is the Bohemian lifestyle that often attends it — that liberated, marginal existence that feeds upon and nourishes creative intensity. The painter Janice Biala (1903–2000) lived such a life and lived it to the very fullest.

Her résumé sounds like a potboiler: Overcoming a precarious childhood, she pursued a seven-decade-long career that spanned the art worlds of both New York and Paris, and befriended many of the giants of art and literature on both sides of the Atlantic. Generous but tough — and always opinionated — she produced a unique body of work reflecting her peripatetic life in the limpid, graceful style of French modernist painting. Her geographical and stylistic distance from the New York School meant that she never achieved the fame of some of her contemporaries, but recent shows of her work at Tibor de Nagy Gallery — where her paintings are currently on view until January 5 — have brought her some long-overdue attention.

Biala was born Schenehaia Tworkovska in a region of eastern Poland historically subject to pogroms. By 1913, she left with her Jewish family for a tenement on New York City’s Lower East Side. (The young girl was later to take her hometown’s name as her own. Her older brother Yakov changed his name, too — to Jack Tworkov.) As a teenager, Biala worked various jobs in order to attend classes at the Art Students League and the National Academy of Design, where she studied with Charles Hawthorne. Edwin Dickinson and William Zorach became her friends and mentors. After a brief and unhappy marriage, Biala left for Paris in 1930, where her encounter with Ford Madox Ford was to change her life.

At age 26, she was less than half the author’s age, but their romantic relationship endured until his death in 1939. For both it marked a time of emotional nourishment and artistic productivity . Through Ford, Biala met such luminaries as Picasso, Matisse, Joyce, and Pound. She later wrote that in living for Ford, she had found herself: “He found a little handful of dust and turned it into a human being.” The comment tells not only of the poignant depth of her love, but also the forthrightness of her self-image. Perhaps, though, she undersold herself: When they met, Ford, an inveterate womanizer, was in a deeply depressive and lonely state. Under Biala’s attention, he regained his writing stride, while Biala managed his contracts and illustrated several of his books. After his death, she became his literary executor, staunchly defending his reputation against the insufficient praise of critics.

When Ford died in 1939, Biala barely had time to secure his papers before the Nazi onslaught. She departed for New York, where her brother Jack Tworkov, now well-connected in the New York art world, introduced her to de Kooning and other future Abstract Expressionists. In 1943, Biala married the French artist Daniel Brustlein, best known to New Yorker readers as the cartoonist Alain. Again, theirs was a mutually supportive relationship, as Biala collaborated with Alain in two-person exhibitions and on a number of children’s books. The couple shuttled between Paris and New York for many years before settling permanently in France.

Over the years they befriended Saul Steinberg, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alberto Giacometti, and Joan Mitchell. Biala’s work, regularly exhibited in Paris and New York galleries since the 1930s, appeared in numerous museum shows. She continued to exhibit to the very end, with her final show at Kouros Gallery in 1999. She died the following year at age 97.

Biala lived as she wished — simply but thoroughly, and in the company of remarkable artists and writers. Spanning nearly 40 years, the paintings and mixed-media collages now on view at Tibor de Nagy Gallery reflect her unpretentious pleasure in her visual surroundings: the street scenes and monuments of France, Spain, Italy, and Morocco. Her admiration for Matisse shows in her simplified descriptions and planes of bright but subtly adjusted colors. In “Bateau sur la Seine” (1980), myriad grays and greens convincingly catch a river’s surface, alternately absorbing and reflecting light. Just two condensations of color punctuate its expanse: a patch of warm white, perfectly capturing a houseboat’s buoyant weight, and the rich, opaque green of a tree’s foliage rising from the near shore. “Open Window” (c. 1989) records a scene reminiscent of Matisse: a window view framed by vertical notes of curtain, wall, and the glass panes of the inward-turned sash. Biala’s hues beautifully convey the illumination of the interior and do so with a self-satisfaction quite alien to Matisse, whose unease disclosed itself in more compulsive contrasts and more swiftly cutting lines. All of Biala’s paintings seem touched by a tough ingenuousness — never sentimental or naïve, but slightly nostalgic in their playful intimacy. Suffusing them is the outlook of a painter who has found what she needs and knows what she wants to do. The results glow with a wondrous candor.

This review accompanied the exhibition Biala: I belong where my easel is… at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, NY, November 15, 2007-January 5, 2008.

Article: Biala paints a picture

The Bull, 1956

Oil on canvas, 43 x 54 3/4 in. (109.2 x 139 cm)

ARTNews

by Eleanor C. Munro

published: April 1956

Once in the course of each of Janice Biala’s paintings occurs that sudden change of process which, in Romantic art, signifies the emergence of insight through layers of reason. “Only in death,” she says, “do you find life” — rephrasing the Romantic gesture of Nietzsche, Wagner and others whose esthetic turns on inspiration. At some point she must “risk the loss of the picture in order to rediscover it,” in its decisive form. This moment took place midway in the evolution of Biala’s latest work, The Bull.

Biala’s creative life, like that of many other artists, swings between polar attitudes. Not unexpectedly, these contrasting moods engender contrasting methods of work, styles and subjects of concentration.

In one world, comparatively serene, Biala paints interiors, still-lifes and beaches. Here compositional balance is of first importance. Long brush strokes, unbroken and graceful, are combined into clearly distinguished and placid areas of dark and light. Behind this style is the commonly accepted tradition of Matisse and Braque.

In the other world, and the one from which The Bull emerges, the key symbol is the bullfight. This is a Romantic world: brush strokes here are broken, coursing, jagged, disconnected, rapid. Colors clash and vibrate: black, red, chalk white, smoky blue. Balance is thrown off; forms lie oblique; the motif itself is swollen with importance, fills the whole canvas.

But even standing in the midst of this world, Biala expressed her discontent with it, and with the Expressionistic, subjective viewpoint in general, with the artist who “sees the world from his own point of view.” Surrounded with the sketches, trials, early stages of this turbulent work-in-progress, she expressed a nostalgia for Classicism and for the style epitomizing for her synthesis of worlds: Chinese painting, where the expressive brush stroke rests in perfect equilibrium. At the same time that Biala was working out her dramatic image in a handwriting completely of the contemporary moment, she made a faint rationalization for this contemporary by quoting Delacroix: “The artist must speak the language of his time… but woe unto him if his time be vulgar.”

In our time, more than one artist of Romantic impulse has found in the bullfight a ritual with suggestive emotional overtones. Hemingway has of course given the bull ring its most famous modern interpretation. Biala, who saw the sport for the first time twenty-odd years ago with her first husband, the author-critic Ford Madox Ford, has returned to it repeatedly since as a subject. She sees in the duel a self-renewing symbol for many conflicts of conscience.

Whatever emotional wellsprings the image taps, it is certain that in this representation of it, many familiar Romantic manners — the spontaneous gesture, the impulsive search for idea, the accidental progress through stages to a revelatory inspiration — were called into play. This canvas was not thought out before it was begun on canvas; it was not approached through a reasoned process of preliminary drawings and transpositions to the canvas. It progressed by apparently disconnected insights.

During the past two years, suggestions of the motif had been several times brought to Biala’s attention. She visited the caves of Lascaux, where the huge prehistoric wall paintings of bulls and other animals made a strong impression. Something of the scale and imposing profile posture of The Bull may stem from those images. Last year in Spain, Biala carried her notebook to the bullfights and made rapid pencil sketches. These were quick and imprecise renderings of shadow and mood; none of them was used directly in this painting, but the spirit they conveyed and the visual memories they called up bolstered the imagination during the course of painting.

When she had selected the motif for this painting, Biala first made a large, quick outline in paint on the canvas, with one of the Chinese brushes she uses for such fast, calligraphic strokes. This outline fixed firmly in her eye the scale and position of the animal; both elements remained unchanged throughout the subsequent four months’ work. They were the architectural piers underneath waves of color and broken forms which swept the canvas surface until resolution was achieved.

Biala next made several rapid and heavy strokes with a wide brush and pure color: strokes which were initial statements of the disposition of masses and accents on the canvas. Like many painters — and their fellow artists before the typewriter — Biala recoils from the empty canvas waiting blank-eyed for the perfectly modulated statement. These first, speedy accents laid the ghost of that fear.

So much achieved, Biala turned from the canvas to pencil and paper. There followed a series of more or less careful pencil studies on paper. These broke the realistic form of the bull down to its component forms in traditional Cubist technique: by analyzing its weights, masses, flanks, planes and lines; redisposing these elements to intensify the patterns and isolate key areas. The disposition of spaces and forms metamorphosed during the studies, until both edges of the area were left more or less empty, while the central forms were strongly broken into angular and sharp patterns. It was at this point that the starlike motif at the top of the bull appeared. Actually a cluster of bandilleros, or spears used to goad the animal in the ring, the star remained a focus or nucleus; and the theme of a sharp, brittle intersection of lines is, in the final composition, stated and varied several times.

Several forays were now made onto the canvas itself, redeveloping the broken forms worked out on paper, developing color relationships and, in particular, distilling the various arabesques which sweep the entire work. On the canvas Biala uses her paint fairly thin; impasto effects are of less interest to her than the richly worked surface of subtly modulated tones. She grinds her own colors in linseed oil, thins them with turpentine and lays them out on a glass palette. During these early stages, when the layers of paint over the canvas are still comparatively few, she tests ideas freely, erasing when necessary with a palette knife, razor blade or sandpaper.

Simultaneously with these excursions on the canvas, Biala experimented with the image in collage. “A collage is meant to come apart,” she says; perhaps for this reason she feels exceptionally free to put one together. Something in the informality and almost infantile insubstantiality of the medium liberates her from restraints self-imposed when she is pace to face with the canvas. The clear, patchy colors of snipped-out paper give her special pleasure, juxtaposed in accidental and suggestive combinations. These subsidiary studies seem to give Biala a chance for pure play; many suddenly arrived-at accents find their way from these papers onto the canvas.

At the same time, whenever a formal problem perplexes the artist, she turns back to the small sketch on paper in pursuit of the solution. Throughout weeks of work, as the broken masses of the bull’s body took form, as the progressions of torn, ripped brush strokes assembled across the lower portions of the painting, the area of the head remained unresolved. Turned in a bland, direct stare outwards, it seemed “too peaceful.” Outweighed by the deep gully across the back, the dredged turbulence of the flanks and the ground on which the bull stands, the area of the head seemed out of balance both formally and emotionally.

Suddenly the problem was solved in one of the subsidiary sketches, when Biala obliterated the features with an extension of the dark mass of the haunches. Taking courage to assault the face with a gash of black, she rediscovered the potency of the image. And in the final analysis, it is a peculiarly menacing, eyeless aspect of this bull which gives the painting its impressiveness.

Thus far, Biala’s technique in achieving the broken, gashed image paralleled her responses to the subject itself. She relates the ritualistic bullfight to the anthropological concept of rites de passage: here, the human step into the realm of unknowable hazard and destiny.

But from the moment of its resolution, the canvas was changed never again in form, but only through minor and isolated color transformations to enrich and intensify its surface. And here Biala protected herself against hazard by a special maneuver: a piece of cellophane pinned over the canvas takes trial passages of color, so that the most subtle relationships can be established before they are transferred to the canvas.

Slight transformations continued to be made on the canvas surface until it was shipped to Biala’s Manhattan gallery. According to her, the painting will “never be finished.” As in free musical improvisation, minor fluctuations of tones can endlessly rove over the surface.

It is possible that some of the pendulating spirit which inhabits Biala’s esthetic is carried over from the early wandering years when her family left Bialystok, a small city in Poland. Even today she is restless: moving between Europe and the United States; moving between her sunny, herb-filled kitchen and the cramped, ex-pony stable, now a studio shared with her painter-cartoonist husband, Daniel Brustlein (Alain of The New Yorker); moving between their middle-class New Jersey community and the artistic world of Manhattan where her brother, the painter Jack Tworkov lives; moving between her dedication to the European models of decorative style, and her embroilment with contemporary New York styles. She is a hard worker, spending as much of every day as possible at the easel; but she takes time off to faire la cuisine like a good French bourgeoisie, and her table is renowned. Her home is neat, to the point of austerity: brown grasses and bowls of dry leaves sift the sunlight into corners of her white living room; but her studio and palette are a jumble of old brushes, pin-ups from art magazines, tentative sketches and works in progress.

Perhaps a good symbol is that heap of crusty brushes: ragged Western ones to stir up the paint surface; sleek, clean Chinese ones to skate blue arabesques across the Bull’s flanks.